Albert Brooks’s films are as smooth and polished as any American comedy could hope to be, and yet they’re freighted with submerged neuroses. Mother embodies this tension between a book and its cover. It has a high concept, the jokes are honed with a jeweler’s precision, and the staging values functionality over poetry. It superficially suggests a sitcom, and yet there’s still very much the possibility of the audience feeling “seen” by Mother, as Brooks’s sharp punchlines are more revealing than they initially appear to be.

One of Brooks’s governing themes here—and perhaps the dominant theme of his work—is how neurotics of his generation try to talk themselves out of their neuroses. Brooks’s characters appear to say what they mean, giving his films a veneer of having no subtext. But his characters’ outbursts, modeled on their generation’s obsession with therapy, grant them nothing. Their theoretically cathartic proclamations are an illusion and they know it, and these nesting layers of self-awareness only deepen the fog of their insecurities.

Early in Mother, John (Brooks), an obscure science-fiction novelist mourning the end of his second marriage, says that he’s attracted to women who don’t believe in him. The intimacy of this admission is startling, and John says it with biting matter-of-factness. The directness of the confession can be read as Brooks simply tending to narrative housekeeping, as the filmmaker needs John to realize his issues with women early on so that he can move in with his mother, Beatrice (Debbie Reynolds), and explore his hang-ups. But there’s an irony underneath the admission, as Brooks understands that John’s straightforwardness is a subtler form of evasion. Admit to your hang-up so you can keep being hung up, only with the fleeting self-satisfaction and illusion of control that come with admitting to it.

Once John drives several hundred miles north from Los Angeles to his childhood home in Sausalito and begins bickering with Beatrice over issues both trivial and enormous, Mother becomes a model of thorny dialogue that cuts in several directions. One of the best exchanges happens over the phone, before John and Beatrice have the opportunity to get on each other’s nerves in person. After a non-start of a conversation, Beatrice tells John that she loves him, and he responds with “I know that you think you do.” That seven-word punchline contains legions: about John’s self-loathing and self-pity, his bitterness, his loneliness, and the gulf between how children and parents, separated by a shifting culture, perceive and express themselves.

But Brooks doesn’t give you time to stew over any line. He’s not a wallower, as Woody Allen once was or as Judd Apatow would prove to be. Brooks hits a line and moves on while you’re still digesting it, and the zingers gather a collective neurotic force. There’s the tension here of hearing something painful and barely being allowed to acknowledge it. Mother’s script, written by Brooks and Monica Johnson, is a marvel of that amusing lines that draw blood upon recollection and of details that embody the gulf between people from different eras who might as well be from opposing dimensions. The film is a loving yet obsessive parody of the generational stereotypes that stand between the Baby Boomers and the Silent Generation.

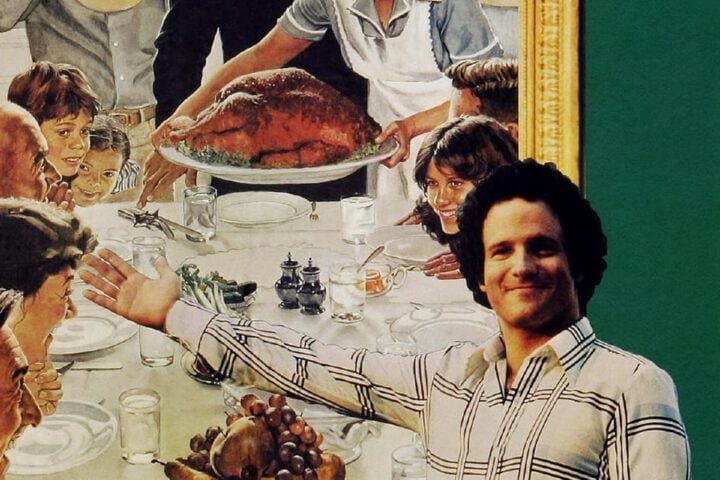

John returns to Beatrice’s home and rebuilds his childhood room and wants them to analyze their relationship for his benefit. Beatrice, who holds her own vast pain and disappointment closer to the vest than her son, sees this behavior as indulgent. In the performance of her career, Reynolds gives her lines ambiguous spins that are tart, loving, sensual and, of course, fearful, suggesting in every utterance the woman that’s kept under wraps at the behest of the role of “mother” and by a fading time that valued low-level terror—of the Depression, of the war—over personal expression. The film’s originality and poignancy are rooted in how Reynolds understands her character’s passive aggression to hurt Beatrice as much as it does John and his more unhinged brother, Jeff (Rob Morrow). It hurts her but she sees no other way. For Beatrice, emotional distance is a means of dignity that’s also a straitjacket.

A difference between Beatrice and many sitcom mothers is that Brooks and Reynolds allow her to “win” a surprising share of the conflicts. In fact, this movie about a lost and hurt man and his mother often tilts you toward the mother. Self-pity and needfulness are hard pills to swallow, perhaps especially when they’re understandable, and John comes on hilariously strong like many a Brooks protagonist. He’s always contriving activities for them to do, he always wants to know what Beatrice is doing, and he takes her need for space as an affront. He’s trying to be good to her and himself in the tradition of many clueless over-achieving adult children in cinema and life alike, and often he only seems to exhaust them both.

One of the film’s most uproarious scenes—an argument between John and Beatrice over her manner of freezing random food for seeming millennia, including salads and sherbet that’s coated in “protective ice”—manages to get you to see things Beatrice’s way even if her way is ridiculous. If she wants to eat cheap crap, that’s her right, isn’t it? No one asked John to live out his midlife crisis in Beatrice’s home after all. (The “protective ice” on the ancient ice cream is one of many details in the film that are so exact as to be universal, and it reminded this reviewer of his own efforts to choke down his grandmother’s infamous “ice milk.”)

The film’s best trick, though, and the greatest measure of love on Brooks’s part as an artist and a son, is that Mother is less about John’s rebirth than Beatrice’s. John’s flailing about is often absurd, but it produces results. He discovers that Beatrice, so critical of John’s obscure novels, was once a writer herself, who stifled that urge to be a homemaker. John says that must be why she resents her children then, as they represent her suppression. In Mother’s most audacious scene, Beatrice unceremoniously agrees, ripping apart the film’s amiable buddy-comedy fabric.

This admission, which flies in the face of what’s “right” for a mother to acknowledge to a child, releases Beatrice and allows her to love John and continue her abandoned work. Such a beautiful irony is worthy of O. Henry and Douglas Sirk, both masters of narratives concerned with social constructs that divorce people from themselves. At the end of Mother, it’s possible after much agony that John and Beatrice can be something besides mother and son: friends.

Image/Sound

In a new interview included with this Criterion disc, Albert Brooks says that he wanted cinematographer Lajos Koltai’s work here to be real yet beautiful, and the 4K restoration of Mother certainly makes it easier to appreciate how that ambition was realized. If you’re accustomed to streaming Mother or watching it on an old DVD, the rich spectrum of dark and burnished colors on display here is going to come as a pleasant revelation. Flesh tones are also detailed, and the lighter colors are soft and elegant. No complaints on the English DTS-HD Master audio track either: Dialogue is crisp and the film’s sound effects, which are important to a couple of memorable punchlines, have been rendered with pleasing depth.

Extras

In a new 25-minute interview, Brooks speaks directly and poignantly of how personal the film is to him in terms of reflecting his relationship with his own mother, actress Thelma Leeds. Brooks also discusses the veteran actresses he spoke to for the titular role, including Doris Day, who decided to remain retired, before landing on Debbie Reynolds via a conversation with her daughter, Carrie Fisher. A brief interview with Rob Morrow is less essential, though charming, and the disc’s booklet includes a perceptive review by critic Carrie Rickey that, among other things, contextualizes Mother within the spectrum of American comedy of the last 50 years.

Overall

Albert Brooks’s sharp, funny and very personal Mother receives a beautiful 4K upgrade from the Criterion Collection, as well as a supplements package that’s lean but appealing.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.