By 1995, David Fincher was an acclaimed music video director whose studio-micromanaged and -mangled foray into feature filmmaking (1992’s Alien³) proved so exasperating and humiliating that he nearly swore off of making full-length movies ever again. But upon being sent a script about a serial killer who commits a series of gruesome, elaborately staged murders, Fincher found himself sufficiently intrigued to take on the project but only if New Line Cinema didn’t compromise the bleakness of the material. He got his way, and a filmmaker seemingly bound to retreat from Hollywood subsequently emerged as one of its brightest stars of the decade.

By 1995, David Fincher was an acclaimed music video director whose studio-micromanaged and -mangled foray into feature filmmaking (1992’s Alien³) proved so exasperating and humiliating that he nearly swore off of making full-length movies ever again. But upon being sent a script about a serial killer who commits a series of gruesome, elaborately staged murders, Fincher found himself sufficiently intrigued to take on the project but only if New Line Cinema didn’t compromise the bleakness of the material. He got his way, and a filmmaker seemingly bound to retreat from Hollywood subsequently emerged as one of its brightest stars of the decade.

Set in an unnamed city so crime-ridden, paranoid, and rotting at the seams that it makes Batman’s Gotham look like Xanadu, Se7en would be bleak and unsettling enough even if it dealt with everyday crime. But the crimes that veteran detective William Somerset (Morgan Freeman) and newly transferred hothead David Mills (Brad Pitt) contend with are particularly heinous. No sooner do the men meet than they are immediately thrust into an investigation into a macabre series of crimes in which the perpetrator murders his victims in accordance with the seven deadly sins: gluttony, greed, sloth, lust, pride, envy, and wrath.

Se7en fits neatly within the mid-’90s zeitgeist of industrial music’s commercial peak in the wake of Nine Inch Nails’s The Downward Spiral. Indeed, the influence of that album and Mark Romanek’s notorious music video for “Closer” can be felt in the iconic opening credits sequence (actually directed by Kyle Cooper of the digital design and advertising agency R/GA) set to Coil’s distended remix of the NIN song. The film proper only extrapolates from the mood intimated by the sequence. Interiors are so dark that it’s as if most of the lightbulbs in the city burned out, and the victims’ homes look disgusting and neglected, regardless of whether they belong to a poor, mentally unstable drug addict or a fat-cat criminal attorney.

If anything, the makeup work on the victims is even more repulsive. An obese man who was forced to eat until his stomach burst has a latticework of stretch marks and varicose veins that resemble the Lichtenberg figure scarring of those who’ve been struck by lightning. The “sloth” victim chained to his bed for a year and emaciated into a living mummy has translucent papyrus skin pulled to the breaking point over a jaw whose individual bones and teeth you can count even with the man’s mouth closed. Never before was the decomposition and indignity of death so nakedly presented in a police procedural, and while it would be easy to see the grotesquerie as nothing more than hollow style, gradually the film’s clinical presentation of the crime scenes reveals a certain sympathy for the victims, given the horrific nature of their deaths.

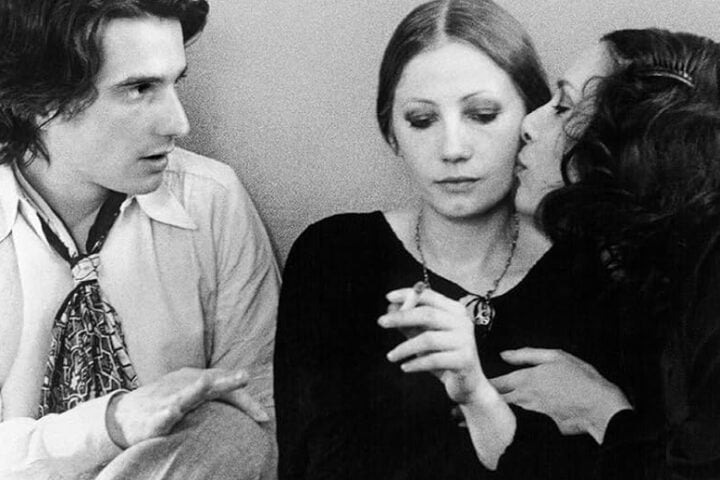

Similarly, Se7en ultimately is elevated by the rapport that develops between Somerset and Mills. Both men are cynical about the prospects of cleaning up the city they serve, but their initial hostility toward one another melts as each sees how the other’s fatalism doesn’t preclude them from doggedly pursuing the killer. Pitt modulates Mills’s cocky, smug attitude as the man slowly comes to appreciate his new partner’s sharp instincts and breadth of knowledge. Somerset’s bleak outlook on life is the result of his innate idealism and desire to believe the best in people being eroded by his job, and he regains some of his optimism seeing the private side of Mills in his doting relationship with wife Tracy (Gwyneth Paltrow).

The warmth that develops between the men is eventually contrasted by their John Doe (Kevin Spacey), whose hatred of the filth around him has manifested brutally but also rendered him completely numb. He speaks in a dull monotone only occasionally enlivened when he taunts his pursuers, and even then his goading has no real note of pleasure in it. It’s just another means of executing his master plan, which culminates in one of the most notorious shock endings in modern cinema, one that seals Se7en in many people’s minds as a work of pure nihilism. And yet, as horrific as the conclusion is, it’s also the final catalyst that shocks Somerset out of his own downturn toward defeatism and back toward a fight, however daunting, for humanity.

Image/Sound

Warner’s 4K transfer is sourced from an in-house restoration approved by David Fincher that used A.I.-assisting imaging software to clean up damage to the negative as well as touch up a few imperfect shots, such as a moment of blurred focus when John Doe is in the back of the detectives’ car, while nonetheless striving to retain the look of a release-night print.

This is easily the best presentation of Darius Khondji’s cinematography, perfectly rendering the film’s dark, metallic images with deep black levels and no crushing artifacts. Detail is razor-sharp even in the most under-lit shots, during which you can make out every grimy texture of crime scenes or every faint discoloration on old reference books that the detectives check out of the library. The film’s color saturation is low by design, but the tints of yellow and green that deepen the sense of rot and putrefaction are as perfectly rendered as the black levels.

The 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio track is, curiously, a downgrade of the 2010 Blu-ray’s 7.1 channel mix. Nonetheless, excellently distributes the subtly discomforting ambient sounds around the front-and-clear dialogue. The bass-heavy drones of the score and city noise are consistently strong and pulsing without ever pushing into outright distortion.

Extras

Warner ports over the extras from its prior home video releases of Se7en, most notably the four commentary tracks. On the first track, Fincher speaks to Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman about their work on the film. For the second, the filmmaker discusses the story with film studies professor Richard Dyer, screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker, editor Richard Francis-Bruce, and Michael De Luca, New Line Cinema’s president of production. The third is focused on the film’s imagery, with Fincher in conversation with Khondji, Dyer, Francis-Bruce, and production designer Arthur Max. Lastly, Fincher discusses the sound of the film alongside Dyer, sound engineer Ren Klyce, and composer Howard Shore. All are richly informative and kept in motion by Fincher’s blend of wry humor and shrewd conversation steering.

Elsewhere are deleted scenes (including the original ending and storyboards for another ending that was never shot); production stills and reproduced photos of John Doe’s victims and crime scenes; and a series of brief featurettes, many of which focus on the opening credits sequence and the extensive storyboarding and experimental techniques that went into its making.

Overall

David Fincher’s Se7en remains as compelling as ever, and Warner’s excellent new transfer presents it in all its grotesque beauty.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.