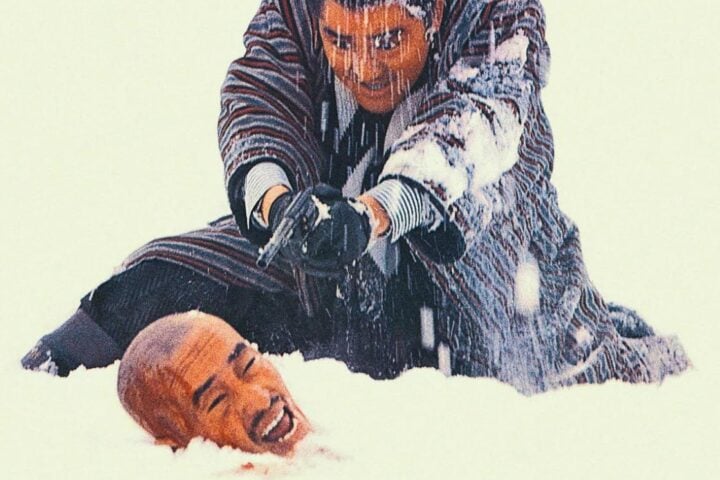

In Fukasaku Kinji’s Sympathy for the Underdog, Tsuruta Kôji’s Gunji walks out of prison after a long sentence and immediately sets out to reclaim turf for his yakuza clan. While Fukasaku’s Japan Organized Crime Boss, from 1969, starts off in similar fashion, with Tsurata’s Tsukamoto receiving a hero’s welcome following his stay in prison, the man looks to keep the peace amid an ever-expanding proxy war between yakuza gangs throughout Japan. He’s principled and, at least in relation to the traditional yakuza code, fiercely honorable, holding true to his word and remaining content for his clan, the Hamanaka Family, to hold on to their territory.

Of course, because the shifting tides of political and social forces in post-war Japan—due in large part to the nation’s wide-scale embracing of Western values and capitalism—are in full force, consolidation and expansion, by any means necessary, is the name of the game. So while seemingly everyone from southern Japan to Tokyo is preparing for battle, Tsukamoto stands as the lone man trying to prevent all-out war between various factions.

As such, Japan Organized Crime Boss is one of Fukasaku’s least nihilistic films, with its chivalrous protagonist upholding the traditional values of the yakuza that were more firmly in place before World War II. And because the delineations between good and evil are more clearly drawn than in Fukasaku’s later films, there’s a bit less moral ambiguity to the proceedings. Yet, there are still moments of surprising tension, particularly between Tsukamoto, our unflappable hero, and the drug-addicted Miyahara (Wakayama Tomisaburô), a crime boss for a rival clan.

Tsukamoto and Miyahara’s unlikely friendship is the most satisfying subplot in the film that too often feels like a more thinly sketched version of Fukasaka’s later yakuza films; even the central love story between Tsukamoto and one of his loyal compatriot’s sisters (Nakahara Sanae) feels perfunctory. Other storylines—particularly one involving a one-armed assassin, Ooba (Andô Noboru)—lean into the type of sentimentality that the filmmaker would soon do away with in his work, though Japan Organized Crime Boss, an early entry in the jitsuroku eiga (“actual record films”) subgenre of yakuza film, is shot through with borderline-genius violent gestures.

Image/Sound

Radiance’s high-def transfer looks very naturalistic, with even skin tones and a wide range of colors. The image is fairly sharp and detail is strong, particularly in the foreground. All signs of damage or debris have been removed, while the grain is consistent throughout. On the audio front, the uncompressed mono track nicely handles all the chaotic sounds in the film’s more violent, action-oriented scenes, while the dialogue is clean and forward in the mix.

Extras

Yakuza cinema expert Nathan Stuart’s video essay covers all the collaborations between Fukasaku Kinji and actor Tsuruta Kôji. He touches on the parallels between the two men’s careers and the evolution of Fukasaku’s themes across his work. In a new interview, film historian Akihiko Ito focuses specifically on Japan Organized Crime Boss, drawing attention to the political subtext of the film and how it helped lay the groundwork for the jitsuroku eiga subgenre of yakuza film. There’s also a 35-minute archival video from 1999 in which Fukasaku lectures a group of businessmen about overcoming adversity. He shares a few funny stories, but overall, it’s a more lightweight extra than the other. Lastly, the disc is accompanied by a booklet, with an archival film review by Ishiko Jun and a wonderful essay by Stuart Galbraith IV that praises the film’s performances and provides background on the various actors.

Overall

Fukasaku Kinji’s transitional film, an early entry in the jitsuroku eiga subgenre of yakuza film, gets a solid transfer and a small but informative batch of extras courtesy of Radiance Films.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.