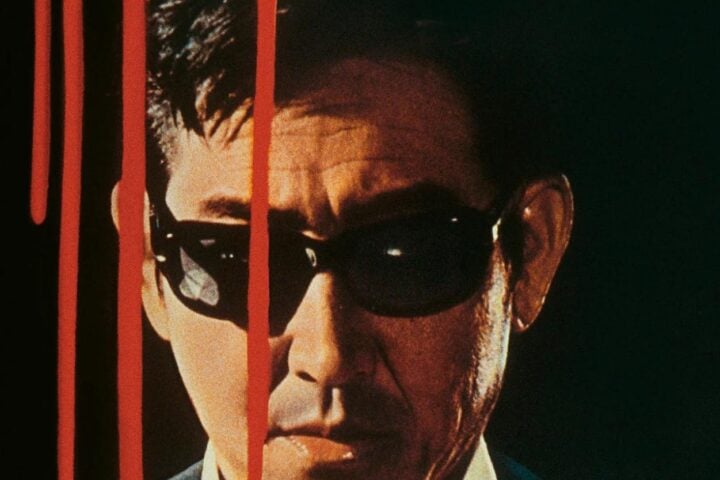

Before his commercial breakthrough with 1963’s Youth of the Beast, Suzuki Seijun made a slew of more conventional B movies for Nikkatsu. Along with films like Eight Hours of Terror and Take Aim at the Police Van, Underworld Beauty is one that showed some distinct traces of the iconoclast that he would become. And the film’s underlying nihilistic worldview and atypically rowdy and abrasive female lead—a young nude model named Akiko (Shiraki Mari)—make it evident that, even in 1958, Suzuki was already on the same wavelength as other future Japanese New Wave directors from the get-go.

Before his commercial breakthrough with 1963’s Youth of the Beast, Suzuki Seijun made a slew of more conventional B movies for Nikkatsu. Along with films like Eight Hours of Terror and Take Aim at the Police Van, Underworld Beauty is one that showed some distinct traces of the iconoclast that he would become. And the film’s underlying nihilistic worldview and atypically rowdy and abrasive female lead—a young nude model named Akiko (Shiraki Mari)—make it evident that, even in 1958, Suzuki was already on the same wavelength as other future Japanese New Wave directors from the get-go.

As is often the case with Suzuki, the plot of Underworld Beauty is decidedly beside the point, involving several diamonds that various members of the yakuza end up fighting over. There’s an impishness and morbid absurdity ingrained in the grotesque journey that these diamonds take throughout the film. The stolen gems first turn up behind a loose brick in the sewers—where the stone-faced Miyamoto (Mizushima Michitarô) stashed them before getting caught and sent to the joint for a few years. Then they’re swallowed by his buddy Mihara (Abe Tôru) before he leaps to his death and—after being, well, extracted—eventually make their way into the breast of a plaster mannequin.

In this underworld of greed and violence, Miyamoto is the only one whose actions are informed by moral considerations, as his initial goal was to sell the diamonds to help Mihara, who’s been struggling with a bum leg since he took a bullet in the initial heist. And later, he works to protect his buddy’s sister, the aforementioned Akiko, after she gets dragged into the whole charade.

The aging lone wolf ingratiating himself with a wild ingénue feels a bit old-fashioned, especially in a time when Japanese films were beginning to reject the cinematic and social norms and traditions of what came before them. However, the film’s vision of the pervasiveness of greed, which is exercised by more than the yakuza, stands as a timely indictment of the rise of Japanese materialism in the early years of the country’s full-on embrace of capitalism.

Underworld Beauty’s best sequence is one of pure, protracted formal prowess: the 10-minute, action-laden finale in which Miyamoto and Akiko are trapped in a basement. The steady array of flying bullets and exploding boiler tanks are intensified by the visual dynamism of Suzuki’s off-kilter compositions and his longtime editor Suzuki Akira’s typically sharp, disjunctive editing as our antiheroic pair dig through mounds of coal to find an escape route. The final beat is a fittingly ironic capper that both highlights the futility of all the infighting, double-crossing, and hyperviolence on display and comically punctuates the utter folly of everyone’s rapaciousness.

Image/Sound

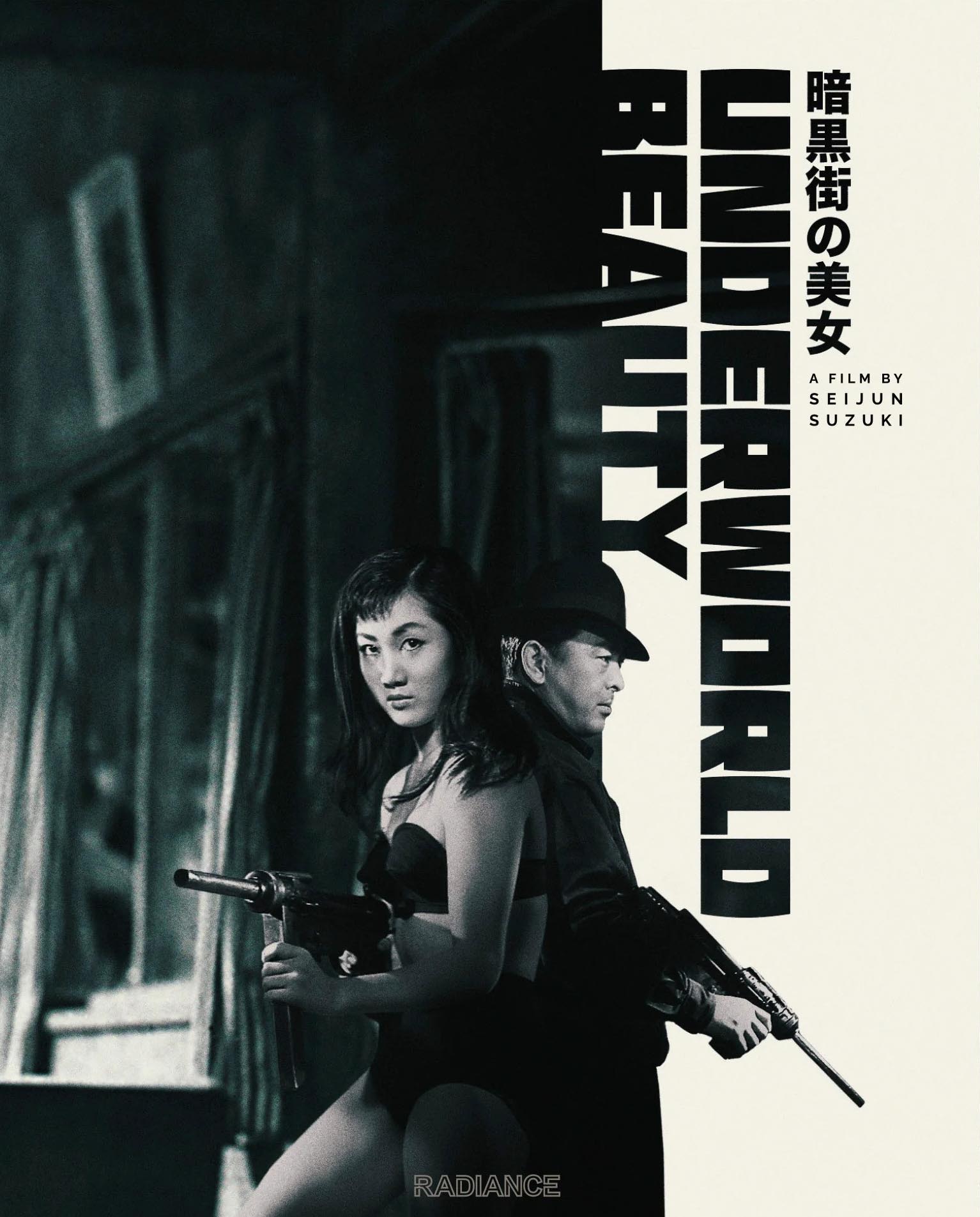

Radiance’s transfer of a new 4K restoration is quite impressive, featuring tight, even grain and a high contrast ratio that captures the intricacies of Suzuki Seijun’s delicate play of shadow and light. Image detail is strong throughout, with the only minor drawback being the occasional fleck of damage, but these are so small and infrequent as to be almost completely negligible. On the audio front, the uncompressed mono track features perfectly clean dialogue that’s always at the forefront, even in the more action-driven shootout sequences.

Extras

In a fantastic new interview, critic Mizuki Kodama discusses Underworld Beauty’s challenging of Japanese beauty standards and branches out to discuss sexuality and eroticism in numerous later Suzuki films. She also talks about Mari Shiraki’s career and the physicality she brings to the screen. The disc also includes Suzuki’s 40-minute 1959 romantic melodrama “Love Letter,” which comes with a commentary by Suzuki biographer William Carroll that touches on the film’s unusual qualities and draws intriguing parallels between this short film and Suzuki’s later works. Rounding out the package is a booklet with a brief archival review and a new essay from critic Claudia Siefen-Leitich that focuses on the film’s use of black-and-white cinematography.

Overall

Including an illuminating new interview and an extremely atypical Suzuki short film, Radiance’s release provides a compelling look at the early career of the Japanese enfant terrible.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.