In the opening scene of the 1957 western The Tall T, a man on horseback is spotted from afar by a boy and his father, prompting the elder homesteader to fetch his rifle. The audience shares their uncertainty, seeing this figure through a telephoto lens from a great distance, but when the stranger gets closer to the ranch, he’s recognized by the boy as an ally.

It’s the film’s hero, Pat Brennan (Randolph Scott), a fellow rancher, and the gun is therefore set aside. The Tall T is the first in a series of westerns grouped under the name Ranown (after producer Harry Joe Brown and Scott’s production company) that director Budd Boetticher made in the late ’50s and concluded with the release of Comanche Station in 1960, and in this inaugural scene, Boetticher establishes a crucial theme and visual pattern of this spiritually unified set of potboilers. At a distance, danger must be assumed. It’s only up close that a man’s character can be revealed, and even then, trust proves to be an elusive thing.

Starring in all five films, Scott plays loner protagonists who are the subject of such wary scrutiny time and time again, even as he routinely establishes himself as a beacon of moral fiber in a land of treachery and amorality. But Scott’s never an uncomplicated or idealized hero, a notion made apparent through Boetticher’s tendency to bookend each film, no matter how valedictory in its resolution, with shots of Scott isolated within a vast landscape. To have a spine in the old west is to find yourself a lonely chap, or, as the cautious patriarch in The Tall T puts it: “A man shouldn’t oughta be stuck off by hisself in this kinda country.”

Throughout Boetticher’s Ranown westerns—now available on the Criterion Collection—the “kinda country” that this character is referring to is the Eastern Sierras of California, and more specifically the great expanse of lunar rock formations known as the Alabama Hills on the outskirts of Lone Pine. This natural wonder, which sits in the shadow of the tallest peak in the continental United States, Mount Whitney, and mere miles from the Japanese internment camps at Manzanar during World War II, is a place that radiates grandeur and desolation in equal measure. More labyrinthine and claustrophobic than Monument Valley, the land is less a cathedral than a purgatorial space, and it proves a fitting venue for Boetticher’s compressed tales of existential searching, where the challenge of finding one’s place in the immensity of the west is literalized by the jagged rocks and towering peaks that divine one’s path.

This desperate yearn for belonging is central to these films. In each of them, Scott plays a man on the move, dissatisfied with his past life and tentatively grasping for a new one. In 1958’s Buchanan Rides Alone—one of two films, along with 1957’s Decision at Sundown, that gravitate around a town rather than the wilderness—his titular character gets hung up in the fictional border town of Agry following a saloon spat that turns deadly. It’s a sensational scenario that spotlights the greed, corruption, nepotism, and incompetence of the settler mentality.

Nevertheless, Boetticher finds his richest subject in the fleeting friendship shared between Buchanan and a guileless cowboy, Pecos (played by a young L.Q. Jones), who’s been tasked with escorting him out of town and offing him in the desert. A long tracking shot follows Buchanan and Pecos as they chat on horseback in the fading sun about their beloved West Texas origins. Ultimately, Pecos spares his prisoner’s life on account of their shared roots, killing his bloodthirsty cohort instead, and what may initially seem a rather absurd leap in logic is in fact the touching expression of a rare and true sense of belonging.

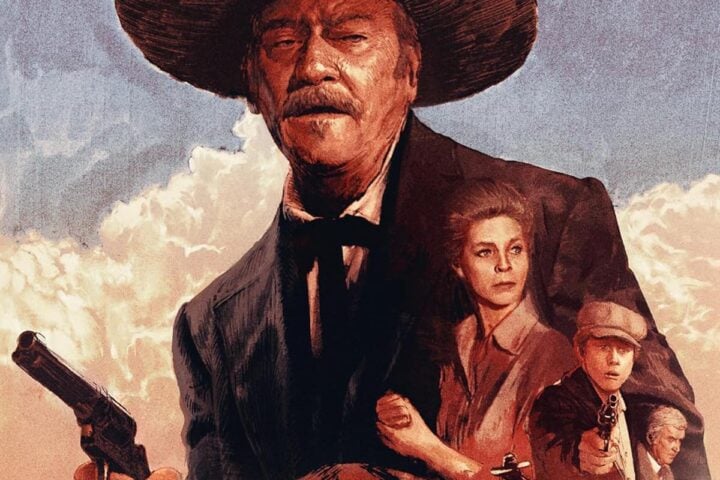

Such fraternal goodwill, though, is a scarce commodity in these films, and more often what looks like decency turns out to be pure callousness. The Tall T offers one of the starker examples of this. Confined mostly to one cluster of rocks where an aging outlaw, Frank Usher (Richard Boone), and his two henchmen, Billy Jack (Skip Homeier) and Chink (Henry Silva), hold an heiress, Doretta Mims (Maureen O’Sullivan), and a rancher, Pat Brennan (Scott), hostage in pursuit of a ransom, the film sets up a Beckettian waiting game in which hero and villain become increasingly enmeshed in their mutual hunger for a peaceful place to live out their days.

The strategic leveling of the expected gulf between good guys and bad guys plays out on a number of levels over the course of the film. There are Boetticher’s deep-focus compositions, which never lose sight of anyone in the small ensemble for very long and often situate characters in triangular formation across the frame, vying equally for our attention. On the script level, there’s an effort to parallel Frank and Pat in their mutual use of equivocating language to obscure their motives and dance around shared dreams of isolating far away from any hardship and corruption. And on an editing level, the film is structured around a democratic distribution of attention given to both captors and captive throughout. Boone’s character evolves from a cold, hardened criminal to a flawed man capable of real vulnerability and eventually back again, but identifying where these elusive shifts take place is ultimately left up to the viewer.

The subtle and serpentine ways in which Boetticher’s characters swerve between civility and pitilessness results in films that burst with suggestive moments that only accrue their full meaning in hindsight. Like The Tall T, 1959’s Ride Lonesome follows five characters brought together by a yearning for financial reward—in this case, for the bounty on the head of a young killer, Billy John (James Best). Scott’s hero aims to escort the kid to Santa Cruz to be hanged, but the danger of the pilgrimage motivates him to enlist a pair of outlaws as travel companions.

The most mysterious of the two, Pernell Roberts’s Sam Boone, speaks almost exclusively in the kind of folksy truisms so often bandied about by Boetticher’s taciturn cowboys to evade emotional transparency or keep their counterparts flummoxed (a prime example: “How a thing can seem one way and then turn out altogether something else”). Here, the chatty stonewalling is so consistent that it implies a man who’s shifting his objectives from scene to scene.

Scott’s Ben Brigade, on the other hand, only utters a word when he feels he needs to. In an emblematic exchange, the lone female in the crew, Mrs. Carrie Lane (Karen Steele), asks him if he’s really the kind of man capable of hunting another for money, to which he simply replies, “I am.” But as usual, Scott’s stoicism gradually reveals bountiful emotional depth, and Ride Lonesome emerges as a study of an inexorably curdling lust for vengeance capped by a potent image of pyrrhic victory: Brigade dwarfed alongside the hanging tree that played a devastating role in his recent past as it becomes engulfed in flames.

For all the prisons that Scott finds himself in throughout the Boetticher canon, from the literal one in Decision at Sundown to the yawning canyons that entrap him on his various journeys, none feel as forlorn as this one. Ironically, In the ceaseless quest for belonging that permeates the Ranown films, the most diverting obstacle proves to be the irrepressible ghosts of the past.

The Ranown Westerns is available now on the Criterion Collection.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

Discovered them a few years ago on the Criterion Channel and found them to be easy, rewarding watches. Something else that binds them is Scott’s willingness to show fear in dangerous situations, something that John Wayne, for instance, would never do. If only we’d chosen Scott as our defining Western archetype — clever and resourceful, absent of bluster, and mortal in the face of danger.

I agree with Sam’s comment on how R,S. portrayals were different for a western star. His characters had flaws and a complicated, mostly unseen past. And some of his characters were conflicted and more understanding of rivals dual characters and their darker sides. But his character was ultimately a good, resolute defender of the right thing to do. I enjoyed his portrayals being different than Wayne’s or Coopers, even though I enjoyed their characters, too. Scott’s westerns, especially the Ranrown collections were more artistic, and I enjoyed all five of them.