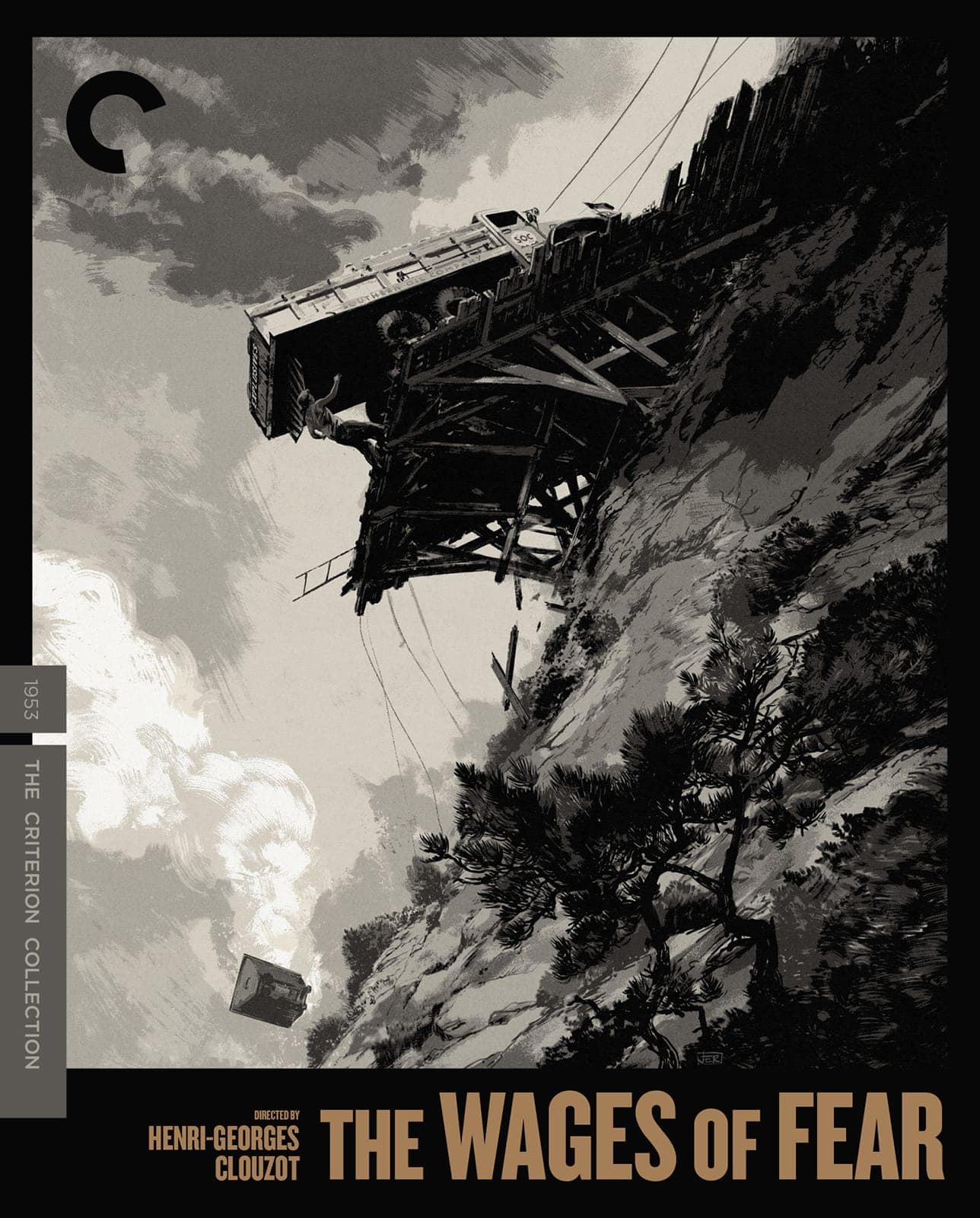

Awarded the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival amid much mouth-frothing from the American press over its alleged communist credentials, Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 classic The Wages of Fear now seems much less like a potboiler spin on Salt of the Earth and a lot more like the spiritual godfather to every testosterone-fueled thrill ride since. Time has inevitably eradicated the contemporary circumstance that fed its political reception and modern audiences will surely recognize that the howls of anti-Americanism said more about the accuser than the accused. If anything, The Wages of Fear now registers as the callous post-World War II flipside to Casablanca, in which people have been scattered not only into pockets of nobility, but also outposts of pusillanimity.

Awarded the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival amid much mouth-frothing from the American press over its alleged communist credentials, Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 classic The Wages of Fear now seems much less like a potboiler spin on Salt of the Earth and a lot more like the spiritual godfather to every testosterone-fueled thrill ride since. Time has inevitably eradicated the contemporary circumstance that fed its political reception and modern audiences will surely recognize that the howls of anti-Americanism said more about the accuser than the accused. If anything, The Wages of Fear now registers as the callous post-World War II flipside to Casablanca, in which people have been scattered not only into pockets of nobility, but also outposts of pusillanimity.

If Diabolique was Clouzot’s bid to out-Hitchcock Hitchcock, then The Wages of Fear is a little bit like a Howard Hawks thriller, only without the mitigating presence of women. The film opens in Las Piedras, a parched, godless shantytown on the outskirts of a South American oil jackpot. There, Clouzot and co-screenwriter Jérôme Géronimi (the nom de plume of his brother Jean) introduce, and in no rush, a rogue’s gallery of international losers that even the Nazis in Argentina wouldn’t have. They spit, steal each other’s clothes, pet women like dogs, and all pine for the chance to scrape together enough bread to make their journey back home, where hopefully everyone has forgotten whatever they did to necessitate their dislocation.

For Frenchmen Mario (a half-surly, half-homoeroticized Yves Montand) and Jo (Charles Vanel), ex-Nazi Dutchman Bimba (Peter Van Eyck), and poor Italian Luigi (Folco Lulli) with his cement-caked lungs, that chance comes when one of the squatting oil conglomerate’s rigs ignites, killing some of the people of Las Piedras. The unwelcome interlopers take the oil company’s fat paycheck to drive a pair of big rigs across a treacherous couple hundred miles to the fire. Their job becomes a grueling journey across a minefield, only the mines are strapped to the insulated flatbeds of their trucks: They’re to deliver massive payloads of nitroglycerin to the site so crews can detonate and extinguish the burning pyre.

Unlike Diabolique, which needed at least some semblance of an empathetic core to justify its protracted “gotcha!” climax, Clouzot’s nihilism distends The Wages of Fear. Literally and figuratively, the four men are lost souls propelled forward not by their belief in the mission, but rather because there’s no other choice but death, either in Las Piedras or holding the steering wheel of a mobile bomb. When their nerves begin to fray and their patience is repeatedly tested, Clouzot presents them without pity, and Jo in particular becomes a whimpering, flatulent jellyfish. Perversely, though, it’s Clouzot’s seeming lack of empathy that allows the four of them to emerge as humans. Sure, they’re cowardly, desperate, and merciless in their pursuit of that $2,000 ticket home, but by God and the Southern Oil Company, they’re alive. Just.

Image/Sound

Sourced from a new 4K digital restoration, this transfer dramatically improves upon the one on Criterion’s 2009 Blu-ray release of the film. Black levels are more stable, and the sharp contrasts between stark, day-lit whites and streaks of inky shadows are even more pronounced than on the earlier disc. Film grain is naturally distributed, and there are no visible signs of print damage. The monaural soundtrack is equally robust, carefully balancing the ample street noise in the early village scenes and emphasizing silence just as much as the groan of truck engines and the unnerving creaks of teetering metal once the main characters’ journey gets underway.

Extras

Aside from an informative new program on The Wages of Fear’s 4K restoration, the disc’s extras have been ported over from Criterion’s earlier releases of the film. These include interviews with assistant director Michel Romanoff and Henri-Georges Clouzot biographer Marc Godin, as well as excerpts of an archival interview with actor Yves Montand; Clouzot’s collaborators recount their work on The Wages of Fear, while Godin places the film in the context of the director’s oeuvre. Also included is the hour-long documentary Henri-Georges Clouzot: The Enlightened Tyrant and an analysis of cuts made to the film for its U.S. release. A booklet contains archival interviews with cast and crew, as well as an essay by crime novelist Dennis Lehane, who unpacks the film’s influence on his work and its virtues as a masterpiece of existential noir.

Overall

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s brutally tense thriller looks better than ever on Criterion’s release.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.