Alessandro Nivola has seen portmanteaus like “Barbenheimer” or “Glicked” and decided to raise a moniker for a triumvirate of his own titles on X: “The Kravenist Next Door.” Across two consecutive weekends, the versatile character actor appears in three films opening in the United States. First, he starred as the comic book villain Rhino in Kraven the Hunter, and he also makes a brief appearance as an interrogating cop at the ending of Pedro Almodóvar’s English-language feature debut The Room Next Door.

But Nivola’s role as Atilla in Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist is the clearest example of why he’s become an actor in such high demand. While this cousin of Adrien Brody’s László Toth only appears at the outset of the film, he casts a long shadow over it. As a Hungarian immigrant to America who precedes László’s arrival by some time, Atilla’s evolutions of identity and ideology illuminate the film’s skeptical attitude about the possibility of assimilation and acceptance.

Nivola, one of the earliest actors attached to the film, adds rich texture and detail to a character who could easily come across as a simplistic cautionary tale or foil to László. His work embodies in microcosm the contradictions and complexities that Corbet’s opus scrutinizes throughout.

I spoke with Nivola amid the whirlwind of launching three movies simultaneously. Our talk covered how he built Atilla from the hints in the screenplay, where he saw connections to his own life in the character, and what resonance László’s story holds for him as an artist.

I find it amusing that The Brutalist, where you appear in the opening act, and The Room Next Door, where you appear in the closer, will come out on the same day. When you’re getting the offers for bookending parts like these, are you reading the whole script to see how your characters function as part of the larger whole?

Well, yes and no. I can’t lump them together just because [my role in] The Brutalist is much more complex, important, and nuanced, [as it] helps tell the story [more] than the bookend of the Almodóvar movie. I had a different relationship and way into both those projects. Brady got in touch with me the second week of the Covid lockdown. I had just stashed my cannellini beans and was preparing for the long, hard winter, and he said, “Oh, we’re filming in Poland in three weeks. Would you like to join us?” It was a totally different cast, but I couldn’t believe that there was a movie being made at all. I read [the script], and there was a whole exchange between me and Brady about how he saw the role and how I saw the potential for the role.

With the Almodóvar movie, he just reached out to the agents and [asked] if I would cameo in his movie. And I said, “I don’t even need to read the script, of course, I’ll do it.” Julianne [Moore] is a friend, and [John] Turturro is. I knew he was doing a little role in it, and so it wasn’t even a conversation. I just said yes, and I had no idea what the script was. It wasn’t until after I had a look and tried to understand what the function of that scene was. But no question, in anything I’m in, the first question is: What do I need to do to help tell this story?

What was your initial read on Attila? Though he exits the film early, he looms large—and it’s meaningful when László evokes his name in the fight with Erzsébet.

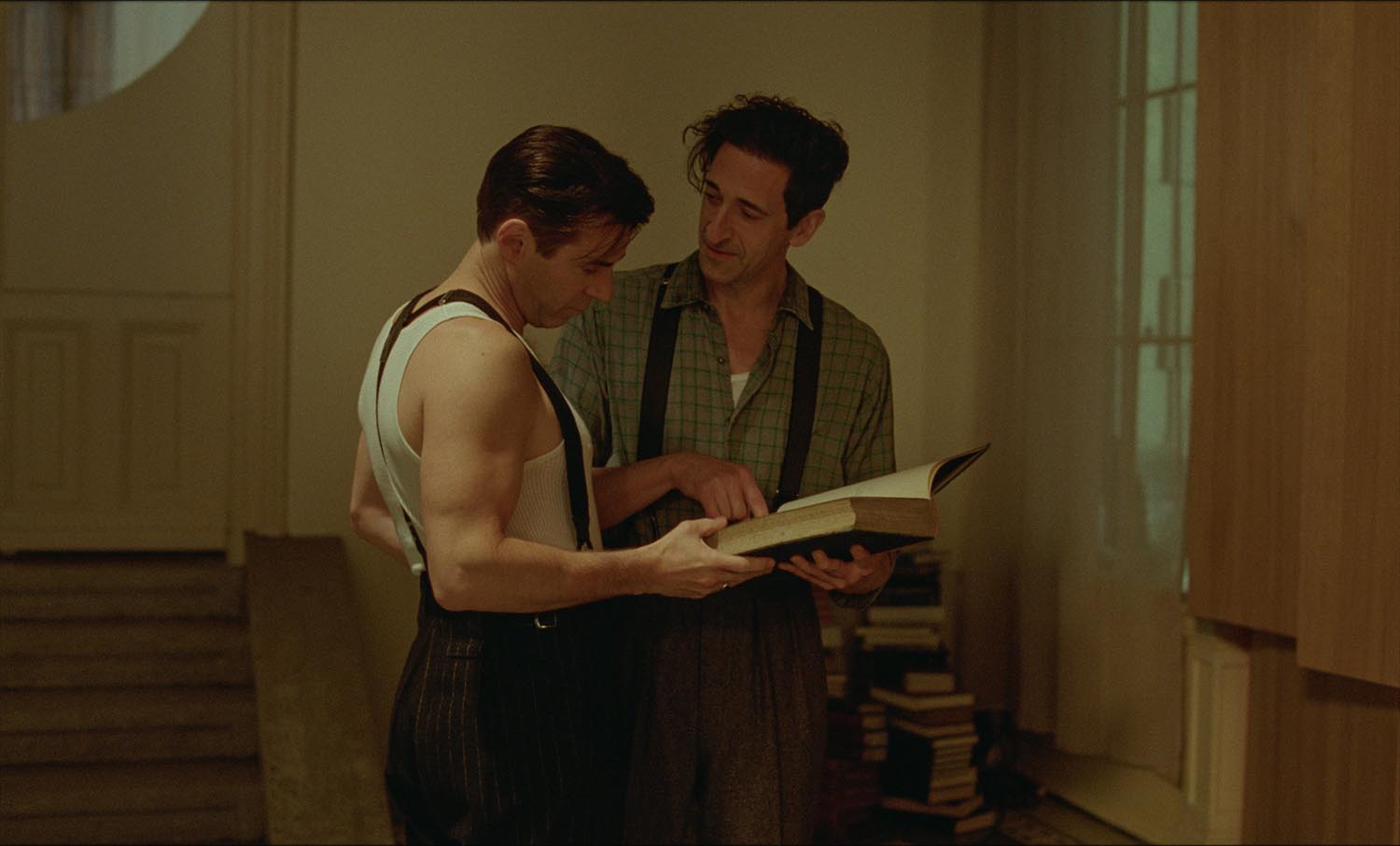

It’s funny because the whole first 45 minutes of The Brutalist is this film with me and Adrien. In any other movie that would be half the film! [laughs] In this one, it’s like a distant memory by the time you get to the end. First of all, I see the story between him and László almost functioning as a film unto itself. Like a film within the film, it has a beginning, a middle, and an end. The relationships are fully developed, and it serves as a kind of prologue to the film that establishes all the themes that will then reverberate through the rest of it.

The relationship is full of emotional crosscurrents. From all the hints that you get from what was on the page, the feeling was that he and I had grown up together, almost as brothers. Our two families were probably close and saw a lot of each other in Budapest. I imagine that Attila admired László’s genius, talent, the confidence of his bearing, and his way with women. All of those things, I think he was probably awestruck by and then also extremely jealous and resentful of. I say in that last scene between us that he had either stolen a girlfriend or slept with her, so there’s clearly this strong current of sexual jealousy there. But he’s family, and I love him.

And, on top of everything, I’ve got this real shame and humiliation for having escaped the Holocaust and the camps. When you first meet the two of us, [László] has just come from hell, and I avoided the whole thing by coming to America 10 years earlier. So I think there’s a feeling of emasculation from that—that I didn’t have to suffer and almost like I’m less of a man or something. And I’m just so desperate to prove to László that I have made it in America, that I’ve cracked the system, that I know how it works, that I’m au fait with it all, that I have the lingo…and it’s all bullshit. László sees right through it, which, of course, is infuriating as well. All those things were going on at once, which was what I found to be enticing about the role.

You mentioned there being hints on the page. What was most helpful for you to build on as you were fleshing out the character?

You always want to ground everything in what’s there, but then the whole joy of it is letting your imagination run wild and getting detailed and specific in your own head about what your experience and relationships had been with all the different people in the movie around you. Tangible things root you in some invented reality that you create for yourself. One of the things that I often start with in all of the performances that I’ve done is vocal stuff. There’s a line early on where [László] says to my wife, “Look at this guy, he sounds like a real American!” And she says, “He doesn’t sound like any American I’ve ever heard.” So that was like an interesting thing to try and find, a voice of somebody who was trying to sound colloquial using urban, East Coast idioms and getting it slightly wrong. Stressing the wrong syllable or word gives him away.

So I was looking for examples of that with Hungarian people who had been living in America, and it turns out there were a lot of Hungarian cinematographers who came to America. I started looking at interviews with a lot of them, and I found one guy named Andrew Laszlo who shot The Warriors and the original Shōgun. Interestingly, I’ve changed my name in the movie from Molnar to Miller, and Andrew Laszlo was originally László András. He was a wonderful guy, and he sounded kind of like a New York, East Coast, cool city guy, but then there were these weird things that he did where he would stress the wrong word here and there. Suddenly, you’re like, “Yeah, it’s not quite right.” I started with that, and it opened a lot of doors in terms of understanding how hard this guy was trying to assimilate.

You’ve told the story of how your father tried to shed his connections to Italy so he could remake himself as an American. Did any of that inform how you interpreted Atilla, and did it help you understand your own history any differently?

I have so many parallel stories on my father’s side of the family to the stories of this movie. My grandmother was a German Jewish Holocaust refugee. She fled Germany in the early ’30s and grew up in Turin in her teens. Then, she met my grandfather, who was a Sardinian sculptor, at art school in Milan before they escaped here at the beginning of the war when they were told by a best friend that they were being informed on. They were going to be arrested in the morning, and it was very dramatic when they came to New York in the ’40s. My grandmother was a bourgeois German Jew who was very well educated, played instruments, was a great artist, and was a bohemian. My grandfather was from much more humble stock in Sardinia as the son of a stone mason, but he had gone to art school and was an autodidact.

Like László and Erszébet, they were both cultured people, and they worked as janitors in a hospital. And then, on top of all that, my grandfather was best friends with the architect who’s considered the father of brutalism, Le Corbusier. He used to stay with them in their house in Long Island for long stretches and once painted these two huge central walls of the house with these beautiful murals that he just painted right onto the walls. They’re still there, and I grew up staring at them all through my childhood. There was so much to draw on just from that.

My grandparents were part of this bohemian artist community out in Long Island with a lot of European expats like Rothko, Steinberg, and de Kooning, as well as Americans like Pollock. That was a different scene, but my dad was trying to be a preppy American. He became an academic, went to boarding school, and then Harvard. He was a wop there, and he had changed his name from Pietro to Pete when he was in high school and boarding school. He wanted to be accepted in that world, and that was a bigger challenge than it had been for my grandparents.

Are you able to carry over any accumulated knowledge from films you’ve starred in like Disobedience or those you’ve produced like To Dust to inform playing a character like Atilla with a strained relationship to Judaism?

Disobedience was the first time I had a close encounter with Jewish orthodoxy, and it was such a deep dive. I became close friends with a Lubavitch Orthodox guy here in Crown Heights and spent a lot of time with his family. They invited me to all their Shabbos dinners, and then he had relatives there over in London who I was put in touch with. I was invited into a community that a lot of people feel is pretty closed. I found it to be surprisingly welcoming, warm, and even boozy. What I kind of collected in terms of experience on that job could only inform me any time I was playing any role that had even a brush with Judaism. The fun of this whole guy was just how much he was trying to transform his own personal history and everything about his own culture into something completely alien to him—and the varying degrees of success that he had.

The Brutalist is just the latest of projects you’ve been in that take America as their subject—such American Hustle, A Most Violent Year, and Selma. What do you take away about the national character from these films that interrogate it?

I had never put that thread together, but I love it. Well, each of those movies had a different perspective on America as a nation and on its history and its character. But if there’s a common thread from all those movies, it’s that it’s just still a little bit like the Wild West. There’s a hidden class system in America that people pretend doesn’t exist. I’ve spent so much time in England as well because my wife is English, and they all talk about America as if the class system doesn’t exist because it’s not talked about as overtly as it is in the U.K.

But certainly, those [and other films] highlight the ways [the class system] is a part of the fabric of the lives [of those] who live or move here. A lot of them are about underdogs, people from an underclass, or immigrants trying to make it—and the degree to which the American dream exists and is possible or not. Certainly, most of these characters have extreme odds against them in trying to make it happen. But, then again, László does [make it happen] in this movie.

László’s story carries wide resonance for artists of all stripes. How do you feel your craft connected to his struggles and successes in The Brutalist?

Brady, in our first conversation, said, “I want to make a movie about an artist getting fucked by his patron.”

Literally.

That, maybe less literally, did resonate! The artistic life is a daily battle. Always has been, and always will be.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.