Even though it also concerns an architect fighting entrenched elites to achieve his singular vision, Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist doesn’t bow before the altar of The Fountainhead. Yet he takes a gauntlet thrown down early in King Vidor’s 1949 film adaptation of Ayn Rand’s novel—no place originally exists in architecture, and the past cannot be improved upon—more seriously than either artist. Corbet’s epic, like Adrien Brody’s László Toth, remains unconcerned with choosing between honoring the past and catering to the present. They instead seek to transcend time altogether, thus equipping their artistry to endure well into the future.

Corbet’s multi-decade survey of post-war America captures the sweeping scope of the novelistic period epics of the studio era, which embodied the cultural might of the United States as it asserted dominance across the globe. But The Brutalist rises above simple pastiche or homage.

The film exists more as a question than a declaration, so the closest it has to a thesis would be the dizzying shot of the Statue of Liberty as László emerges from the hold of the ship bringing him to America. Cinematographer Lol Crowley shoots New York’s beacon of welcome as the exhausted immigrant would view it: first upside-down, then perpendicularly. Shifting viewers’ perspectives on the physical projections of power and promise portends a feature packed with potent reconfigurations of established national iconography.

The Brutalist doesn’t tweak the structure of an old studio style so much as it exposes it, like the buildings in the titular architectural style do with their constructions. Against the backdrop of a colossal cinematic canvas, Corbet has allowed himself the space to explore America not as a series of competing dialectics but as a set of coexisting contradictions. László’s dogged determination to realize his singular vision of a vibrant community center in suburban Pennsylvania exposes foundational paradoxes that make up the bedrock of American life.

Brody’s performance gathers increasingly tenacious force as he comes to understand that the American promise wasn’t endowed to him upon his arrival at Ellis Island. Instead, it’s earned with tremendous work against overwhelming odds. Across the wide span of The Brutalist, Corbet and Brody capture the many facets of László’s brilliance and brashness. He’s no one’s idea of the “ideal immigrant” trope that permeated Trump-era culture.

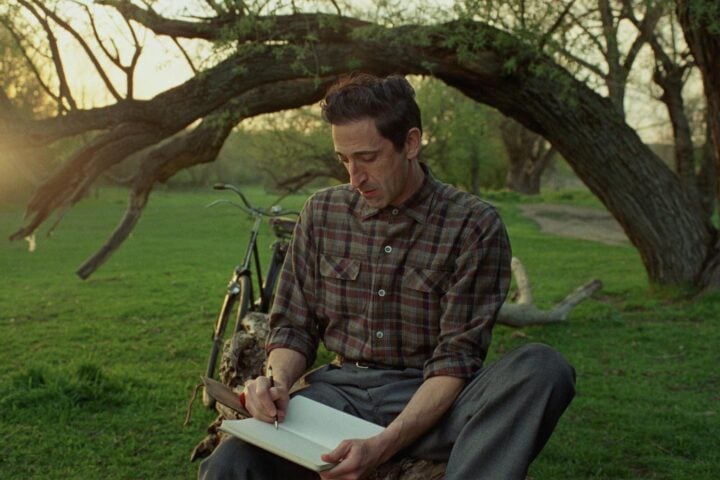

At his core, László is a dogged dreamer with the foresight to build structures that can withstand the ravages of both man and nature. Within his work, he looks to create spaces that can endow a sense of connection between people. (A running joke about his slumming it by working on a bowling alley, that great site of mid-century American socializing, only underscores his commitment.) As someone redrawn out of his birth country and left with little choice but to flee Hungary following the Shoah, László understands that true freedom and belonging cannot be proscribed within arbitrary, fungible national borders. Home isn’t given through American migration or, later, through his family’s Zionist impulse for Israeli repatriation. It’s built.

László’s magnum opus, the construction of which lies at the heart of The Brutalist’s narrative, provides an opportunity for both his most personal and functional work. It’s the culmination of his interest in secular and sacred communion, as it combines a church, a library, a gymnasium, and an auditorium. And yet, his struggle to complete the project reveals the challenges inherent in trying to bridge the oxymoronic nature of funding the public good through private enterprise.

The community center commission arises through a landed businessman, Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce), as a memorial to his late mother. While their first interaction comes through a renovation of Harrison’s home library—a surprise gift by his son, Harry Lee (Joe Alwyn), that goes awry—catches him unprepared with its minimalist stylings, he eventually comes to appreciate the design’s forcing of perspective. As the Van Buren family’s benefaction engulfs him, László comes to understand the shared root of “patronage” and “patronizing.”

László and Harrison Lee aren’t obvious foils, though Corbet and co-writer Mona Fastvold foreshadow their eventual discord with the smallest detail of how the Van Buren family built their fortune: wartime manufacturing. Destruction begetting construction makes for strange bedfellows, though László hardly needs them for obstacles to plague the project. Perfectionism isn’t the builder’s only vice, as he struggles with alcohol and heroin, and he’s not above some womanizing while he awaits the emigration of his wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones).

Her eventual arrival with her sister’s orphaned daughter, Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy), only serves to lay bare the cracks in the foundation of László’s undertaking as he begins to encounter resistance from both the community and the corporate interests backing the build. The coexistence between past and present, which he tries to achieve in his work, becomes difficult to sustain in his relationship as vestiges of the life he left behind wash ashore. “Haven’t you told them anything about me?” Erzsébet prods her husband after she’s left to provide basic details about her background to people who’ve known László for years. It’s but one of many instances where the ideals upheld by art prove incompatible with the realities of American life.

László’s story maps neither to a tragic nor a triumphalist arc as his inspired idealism dissipates into irascible individualism. He quickly learns where the elite draw demarcations of whiteness and wealth—close enough to benefit from his intelligence, far enough to remain mostly invisible. And without hammering the budding alliance between Black and Jewish Americans too forcefully, the intermittent presence of Isaach de Bankolé’s laboring partner Gordon serves as a constant counterpoint to any illusions László might have about unconditional freedom.

Though The Brutalist draws a subtle parallel between the strength of Pennsylvania’s steel exports and their Jewish imports, Corbet demonstrates the limits of a diverse community’s resolve and resilience in the face of hegemonic power. Assimilation is just accommodation, not acceptance. In one of the exceedingly few on-the-nose moments during The Brutalist’s running time, Harry hammers this home by warning László: “We tolerate you.”

The America of the film is a jealous god requiring ritual sacrifice to achieve one’s destiny. The promises of her bountiful blessings give way to a possessiveness that Corbet captures in several fleeting—but chilling—montages of ordinary people clutching their belongings despite facing no real threat of theft. László’s story both fulfills and repudiates the post-war promises of a nation, a feature which ensures he’s never reducible to the simple embodiment of a philosophy. He’s an imperfect but never inconsistent protagonist, which is part of why his jagged edges mesh so well with the airtight construction of the film. Corbet builds on celluloid what László does with concrete: an unvarnished monument to the authentic American character.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.