One would think that after venturing hundreds of miles from home, fighting through Hel, slaying gods and monsters of all shapes and sizes, all while struggling with PTSD and psychosis, Senua might be willing to find a nice place to settle down and live out her days. But, no, Senua’s Saga: Hellblade II finds its Pict warrior heroine going off to Iceland with a half-baked plan of letting herself get captured so she can trace the slavers who tortured and murdered her people back to their source. Right idea, good intentions, but the execution leaves something to be desired. As it turns out, that’s basically a perfect summation of this game.

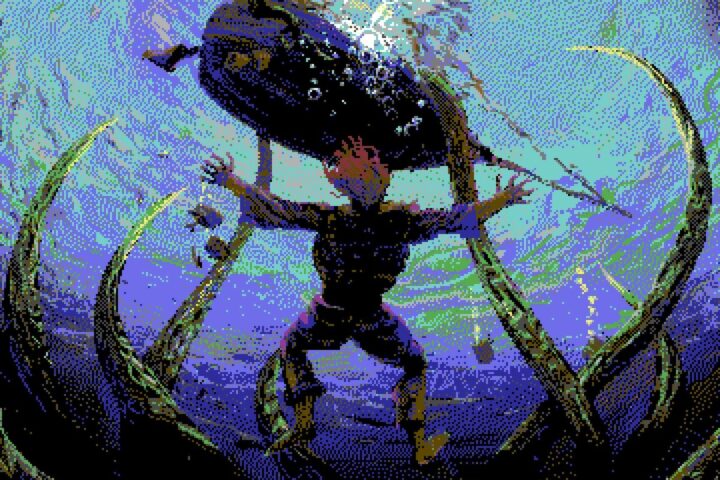

Trying to make a sequel to a game that literally went to hell and back is a dicey proposition. To their credit, the folks at Ninja Theory do make the right call here: Senua’s new journey is less about a grand all-encompassing odyssey than about her genuinely altruistic need to use what she’s learned about herself and her mental illness to help others. Yes, she’s still got to take up the sword from time to time, and also to Ninja Theory’s credit, Hellblade II is home to some of the most primal, weighty, and barbaric swordfights ever committed to a game.

But like much of the evil that permeates Senua’s world, pulling the sword always feels like an act of desperation. A great deal of the game’s story is Senua fighting her need for righteous vengeance to try and demonstrate that catharsis can come from elsewhere: from mercy, from grace, from forgiveness, even as she struggles to give herself those things.

Given just how unrelentingly grim Hellblade II can be at times, making genuine healing a core tenet of the game is a beautiful thing, especially since that healing, the sheer power of someone feeling seen and heard, is the key mechanic guiding the biggest set pieces in the game. But actually executing on it is undoubtedly difficult, and this is where the game stumbles.

The crucial problem is just how incohesive Hellblade II often feels. From the big, visually audacious set pieces where Senua meets the giants of Jotunheim, to the excellent brain-and-world-bending puzzles, to the bloody action sequences against the otherworldly, flesh-eating Draugr, everything here is polished and cared for but at the expense of the building blocks the narrative needs to pay off emotionally. Even with Senua’s illness, this is a narrative that relies so much on characters needing to be open and vulnerable with each other, and these people barely talk to each other except to relay the bare minimum about how their people are suffering.

Aside from the companions that Senua picks up across the game’s campaign, each with fractured narratives all their own, we see so little of Senua actually being part of a community again, relating to it. There’s so little space given for her and her illness to interact with people, despite the narrative hinging on Senua having enough of a connection to people to fight and grieve for them. We can believe that she has a generalized empathy for the people living under the giants’ threat but not to the extent that she has an emotional break seeing dead bodies, especially given that she spent a chunk of the previous game wading through a river of them.

It’s hard to shake the feeling that vital connective tissue has been stripped from Hellblade II’s narrative. People who can help Senua will be mentioned, and never met. Tribes and villages in danger from giant attacks will be mentioned but never visited. A seemingly branching decision moment in a haunted forest has no payoff. That feeling is especially pervasive as the game reaches its apex, a rushed conclusion that does have a few powerful character moments for Senua, and makes a hell of a statement about how monsters are created.

That’s too bad, because the first Hellblade is a focused, frightening masterpiece that earns its catharsis through screaming, fire, and ultimately a sacrifice that is fully in the player’s power to give. Here, the credits roll before you can even process what we’ve learned. If Senua’s saga is indeed what counts for therapy in her blood-soaked world, far too much of Hellblade II feels like she walked out of her sessions with time left on the clock.

This game was reviewed with code provided by Assembly.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.

it’s missing rather more than that.

all atmosphere and no gameplay. the game is only about 5-6 hours long and is you subtracted the cutscenes and the time you listerally are just walking there’s little more than an hour of “gameplay”.

All very well boring how cinematic it is, and that’s true, but ultimately it is a game and a such is pretty poor