In three separate realms, Tales of Kenzera begins as a story of loss. In the real world, Surgent Studios’s CEO and creative director, Abubakar Salim, lost his father, sparking a need to create an outlet for his grief. In the game itself, Zuberi, a young man of the Afrofuturist utopia of Amani, has lost his own father and is gifted a book of myths that was written by the man as he was dying so that his son could cope. Finally, the book’s story, and that of the playable narrative, concerns a young shaman named Zau who’s also lost his father.

However, Zau has a more extreme solution to deal with his grief: He seeks out Kalunga, the god of Death in the shape of a tribal elder, and attempts to bargain to bring his father’s soul back from the grave. Kalunga agrees, in exchange for Zau’s help in tracking down three divine spirits across the land who have refused to go gentle into that good night when their time has come.

With that heavy thematic weight, it’s almost a little disappointing that Tales of Kenzera: Zau is, fundamentally, a rather basic Metroidvania, where the game’s platforming and puzzle mechanics don’t do a terrible amount for most of its playtime to link back to the larger story. The hand-to-hand combat, which is mixed with rapid-fire ranged weaponry, does tip its hat quite a bit to the likes of Devil May Cry and Guacamelee!, but it’s missing both those series’ sense of depth, and aside from a couple of shocking and surprisingly tricky boss fights, the enemy variety isn’t wide enough to keep fights from growing a bit staid by the end.

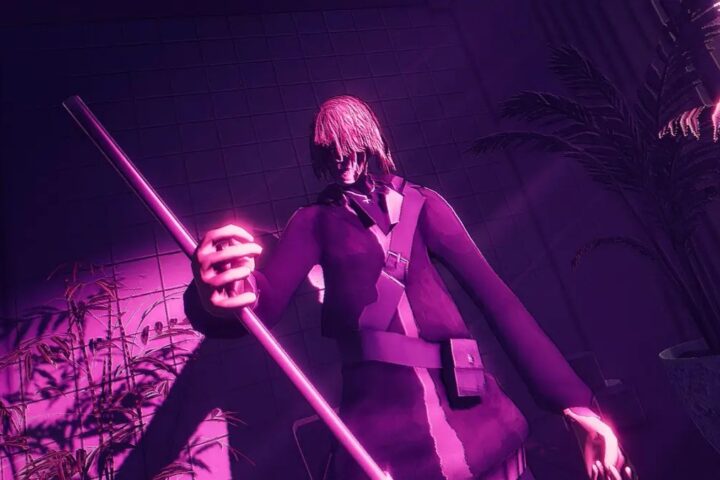

Tales of Kenzera isn’t the most innovative Metroidvania ever made, but it’s pioneering in bringing African lore and storytelling by and for people of color to games in a meaningful way. The aesthetic is extremely beautiful, with its sun- and moon-coded enemies and obstacles bathed in neon oranges and blues, and mythological figures modeled after African masks. It’s also a joy to see Black characters drawn through the eyes of actual people of color—with darker skin, authentic garb, and attentive detail to their hair—and not feel othered because of it all, a factor made even more special by the inclusion of a Kiswahili audio option. The mythology, though pulling names and elements from multiple tribes, will be new to most Western audiences, and the game utilizes their specific history in such distinctive, thoughtful ways.

And yet, the look and feel of the game isn’t nearly as impressive or enduring as its narrative, taking our hero through a whirlwind hellride through the stages of grief. Death himself is Zau’s constant companion in his journey, focusing him on the journey at hand, ever disappointed in his need to prioritize one man’s life against the natural order. Zau’s adventure is, inherently, a fool’s errand but a necessary one for the shaman Zau must become. Zau—and the player—may be playing this game to win, but Death is along for the ride to teach a valuable lesson, one that Black men in particular aren’t typically privy to discuss with loved ones.

If the structure of the game connects in any meaningful way with the theme, it’s this: With every swamp, every desert, every erupting volcano, Zau is forced to process his grief, to assess the motivations for wanting to bring his father back, and figure out the man he must embody to truly win. And the narrative allows Zau to fail, to be petulant and mournful and pissed off in ways that Black men aren’t always allowed to be in reality, let alone games.

That narrative undercurrent makes Tales of Kenzera: Zau’s mechanics and direction less about lack of ambition than accessibility. At a mere 10 hours, this is a game whose brevity is by design. After all, its story is, ultimately, about letting go, about accepting life’s harsh limits, and finding meaning in the time you have. Even as short as Tales of Kenzera is, it speaks in meaningful ways about things that audiences have needed to hear for a long time.

This game was reviewed with code from fortyseven communications.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.