It’s hard to believe the same man directed both the self-deprecatingly nostalgic A Christmas Story and Black Christmas, a twisted little shocker about a killer who infiltrates a sparsely inhabited sorority house at Yuletide. The two films could hardly be farther apart on the Christmas-spirit spectrum. But, then, Bob Clark was a dedicated craftsman who preferred to adapt his style to the subject matter at hand. He began his career as a regional horror filmmaker in Florida, churning out in quick succession Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things and Deathdream, a scathing Vietnam-era twist on “The Monkey’s Paw,” before emigrating to Canada and taking on a script then entitled The Babysitter. Clark extensively reworked the scenario, altered the location, and added in substantial amounts of very black humor.

Based loosely on an urban legend, Black Christmas just may be the perfect antidote to the saccharine sweetness of most Christmastime fare. It’s perhaps best described, in the pungent phraseology of Burt Lancaster’s dictatorial columnist from Sweet Smell of Success, as “a cookie full of arsenic.” Over the course of the film’s charity Christmas party, children are encouraged to knock back alcoholic beverages, and Santa’s cheerless greeting is “Ho, ho, fuck.” Later on, the sorority’s resident vamp regales a dinner party with tales of animal sexual behavior. The vein of vulgar humor running through Black Christmas provides an unexpected link with another Bob Clark film, the archetypal teen sex comedy Porky’s. But the humor here is far less good-natured, and the gags never work to defuse the mounting tension, even if they occasionally threaten to derail the narrative, like the protracted “fellatio exchange” routine.

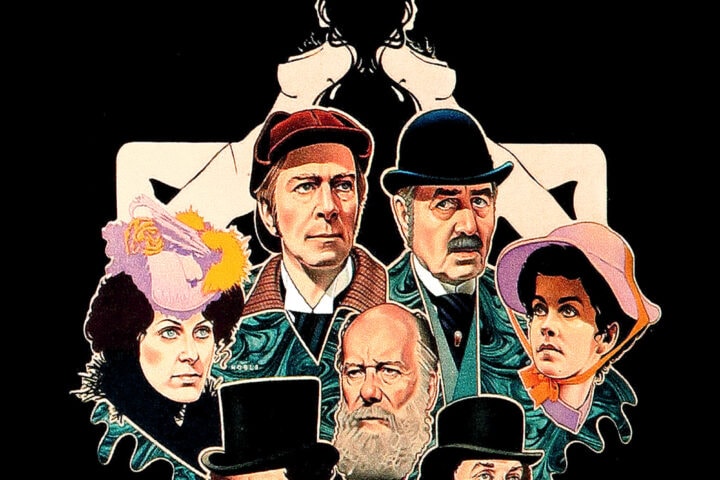

Clark takes the time and trouble to establish his location and fully flesh out his characters before bumping them off. What’s more, these characters are refreshingly complex individuals who do and say unexpected things. Clark’s abetted immeasurably by a strong cast of up-and-comers, blending fledgling stars like Olivia Hussey, Margot Kidder, and Keir Dullea with faces that would soon become familiar from the films of David Cronenberg (particularly Art Hindle and Les Carlson). The film’s sexual politics are also surprisingly progressive: Jess (Hussey) is a strong-willed, independent heroine, who speaks openly and honestly about finding herself pregnant out of wedlock, not wanting to keep the baby, and being unashamed of wanting what she wants. In any other slasher film, either she or Kidder’s brazen hussy would be first on the chopping block, but Black Christmas takes out its chirrupy virgin first.

Black Christmas lays much of the groundwork for the holiday-themed slasher cycle that came into its own four years later with Halloween. (Clark says he gave John Carpenter the basic scenario and even the title for Halloween while sketching out a hypothetical sequel to his film.) Both films open with a faceless killer prowling outside a house, the camera unsettlingly adopting his subjective POV. Clark uses this technique throughout (and to more radical effect) because ultimately his killer is never clearly seen, and his identity is never revealed. The prowler (per the credits) or “Billy”—as he perhaps names himself in a series of disturbingly obscene calls to the sorority girls—is far from the unstoppable boogeyman that Michael Myers represents. He’s an all-too-human killer with unclear, if clearly disturbed, motivations.

Both Halloween and Black Christmas conclude on an ambiguous note of irresolute resolution. Seemingly dead, Michael’s body suddenly disappears, signifying perhaps the indestructibility of pure evil but certainly paving the way for an eventual sequel. Black Christmas’s ending is much more unsettling, as the blame for the killer’s crimes rests firmly on the wrong shoulders, its heroine out cold and completely helpless. And then the camera executes a leisurely dolly back down the hallway, peeking into the rooms where the various sisters met their ends, winding up at the hatchway to the attic as it slowly creaks open. And so we’re left utterly clueless as to what might happen next, once that phone starts endlessly ringing again.

Image/Sound

Shout! Factory may as well have gone ahead and retitled this 4K release Blackest Christmas, because a film that already leaned heavily on the notion that Christmas is where daylight goes to die becomes positively riven with shadows and shade here. One could argue that there are few other films out there that stand to benefit from the format’s capacity for accurate blackness than this one. All the better against which to contrast the pops of incandescent reds and greens from the holiday décor. (The shot of Olivia Hussey standing at the sorority’s front door to listen to carolers, while flanking a wreath lit by a half dozen red bulbs, is a stunning, radiant knockout.)

The transfer, which came from a new HD scan of the original negative, simultaneously pays justice to the rawer edges of the cinematography, such as the film stock appearing to flicker in the shutter during Margot Kidder’s stabbing death. All in all, a transfer so good you feel as though you can smell it. (The set also includes the prior release’s “Critical Mass” transfer in 1.78:1—if you prefer things even danker and more oppressive.)

Even more impressive, especially in light of the previous Blu-ray release, is the restored audio track. Last time out, the soundtrack belied an obvious and clumsy attempt to sweeten the mix, coming off as shrill and distorted. The elements were there, as anyone who has listened to Waxwork Records’s vinyl release of the film’s soundtrack already knows. This time around, sound engineer Brett Cameron went into the trenches to right the wrong. Heady is hardly the word for what he accomplished here. The calls from “Billy” inside the house were already a tough sit in previous editions, but here they’re practically soul-devouring. And, of course, composer Carl Zittrer’s cruel score continues to haunt long after the film’s conclusion.

Extras

Shout! culls virtually every supplement from prior DVD and Blu-ray releases of the film, yielding over five hours’ worth of bonus features, including two interviews with actors Art Hindle and Lynne Griffin—not to mention three separate commentary tracks. (Newly added this go-around is a featurette detailing the painstaking restoration of the audio.) What emerges as you excavate your way through the various strata of supplements is an archeological record replete with overlapping anecdotes as well as nuggets of new insight, stretching back to almost two hours of raw interview footage with Olivia Hussey, Margot Kidder, Art Hindle, John Saxon, and Bob Clark. (Cream of the crop: Kidder confiding, before cackling delightedly, “What a blur it all was!”) Highlights among the extras include pieces on the film’s legacy, the “On Screen!” episode, and the “Revisited” featurette. What’s more, the commentary with Nick Mancuso in character as “Billy” should provide some choice background chatter for your next Christmas party.

Overall

No other Christmas movie captures the disquieting, solstice feel of a subzero pause button being pressed, and few other horror movies so thoroughly embrace the cold.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.