Paranoia, at least the kind stemming from a lack of confidence, isn’t the dominant sensation permeating Oliver Stone’s frenzied and decidedly campy pledge of malignance JFK, the film that briefly made conspiracy theorizing not just socially acceptable, but practically a cornerstone of citizens’ civic duty. No, in practice, JFK is as sure of itself as a QAnon truther, setting into centripetal motion hundreds of specious theories and dancing around the logical gaps like Max Ophüls’s camera did the titular jewelry of The Earrings of Madame de… It’s the crown jewel of the small but potent batch of mainstream American films of the late Boomer era that seemingly rode the collective insanity of the cultural zeitgeist to financial reward and cultural cachet—two other obvious examples being Network, which explicitly “articulated the popular rage” that had more or less been building since the Kennedy assassination, and the late entry The Passion of the Christ, which disguised post-9/11 righteous bloodlust within the oft-declared greatest act of love mankind has ever known.

Paranoia, at least the kind stemming from a lack of confidence, isn’t the dominant sensation permeating Oliver Stone’s frenzied and decidedly campy pledge of malignance JFK, the film that briefly made conspiracy theorizing not just socially acceptable, but practically a cornerstone of citizens’ civic duty. No, in practice, JFK is as sure of itself as a QAnon truther, setting into centripetal motion hundreds of specious theories and dancing around the logical gaps like Max Ophüls’s camera did the titular jewelry of The Earrings of Madame de… It’s the crown jewel of the small but potent batch of mainstream American films of the late Boomer era that seemingly rode the collective insanity of the cultural zeitgeist to financial reward and cultural cachet—two other obvious examples being Network, which explicitly “articulated the popular rage” that had more or less been building since the Kennedy assassination, and the late entry The Passion of the Christ, which disguised post-9/11 righteous bloodlust within the oft-declared greatest act of love mankind has ever known.

For more than three Hard Copy-paced hours, JFK peels back the layers of one of America’s darkest onions, with New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison as Stone’s sous chef. Garrison made waves in 1968 for bringing the first criminal case to trial in Kennedy’s death. Garrison centered his case against Clay Shaw, the effete businessman who defrocked Catholic priest David Ferrie (Joe Pesci) allegedly painted gold while gay hustler Willie O’Keefe (Kevin Bacon) dressed up like Marie Antoinette. (But Stone digresses, and frequently. As O’Keefe informs Garrison at one point, “You don’t know shit ‘cause you’ve never been fucked in the ass!”)

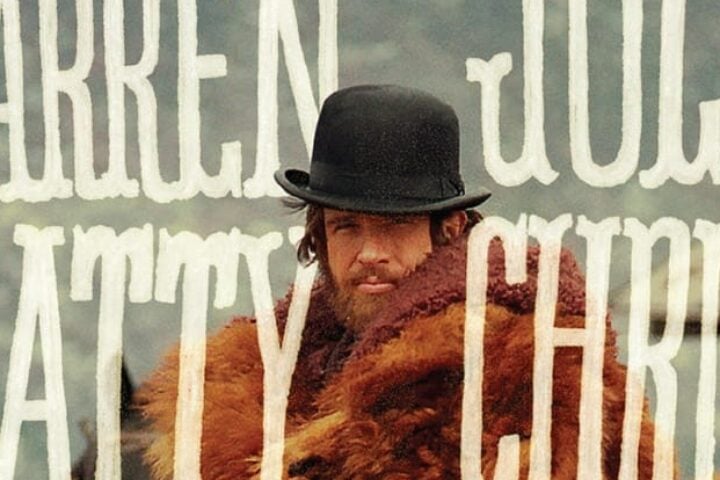

As played by Kevin Costner, notably then America’s most trusted leading man, Garrison is too concerned with the bigger, sloppier picture to concentrate on building a deep case against Shaw, and consequently he loses the battle. Stone, clearly identifying with his protagonist, is convinced that Garrison’s case and JFK itself are but two steps in winning the war. “Let justice be done though the heavens fall,” Garrison snipes during his closing arguments, promising both.

More than three decades later, JFK can clearly be tarred for, well, you name it. It conflates both documented facts and speculative theories through its varied film stocks and dazzlingly edited form. (Sergei Eisenstein would’ve torn apart his popcorn box in envy.) Stone, as evidenced in the massively footnoted shooting script published in accompaniment with the film, clearly never heard the phrase “consider the source.” There are fewer people who are ultimately absolved of guilt in Kennedy’s death than are held in suspect, with extra shade thrown at Cubans, gay men, American communists, recently fired intelligence-department executives, strip-club Svengalis, Lyndon Baines Johnson, faux-epileptics planted along Kennedy’s motorcade route in Dallas, moles within Garrison’s own office, and the alliance that would’ve naturally formed among the entire lot of them—everyone except Gary Oldman’s lazy-eyed patsy Lee Harvey Oswald.

Even more egregious with time is Sissy Spacek grimacing through the thankless role of Garrison’s Stepford-like wife, Liz, a stand-in for people’s inherent skepticism over assassination conspiracies. For all the heat that Christopher Nolan faced over the sausage fest that was Oppenheimer’s cast roster, at least he didn’t force Emily Blunt to utter anything like the howler Liz directs at her husband halfway through his investigation into Shaw: “You’re attacking this man because he’s a homosexual? Did you ever stop to consider for once what he was feeling?”

What JFK can’t be demerited for is offering a simple, staid history lesson. Quite the opposite, as Stone’s film assures audiences that no representation of the largest truths (read: the Warren Commission) will ever actually embody such lofty veracity—which is why you can practically hear Stone licking his lips in casting Garrison himself in a cameo appearance as Earl Warren. It’s both paradoxical and somehow perfect that the film’s reckless blitzkrieg of infotainment is so hypnotically engrossing as to be totally duplicitous.

Never before and never since has such a high-profile appeal for seizing personal responsibility for the information the media feeds us left so little space for individual interpretation. “It’s a mystery wrapped in a riddle inside an enigma,” presumed conspirator Ferrie pathetically weeps when at the end of his short rope. Not really, little man. Through docudrama depiction, JFK spells out each and every claim as though disabusing the American public of every single myth surrounding what happened in Dealey Plaza on November 22, 1963, with a full slate of familiar and comforting movie stars and character actors ready to guide them through the muck.

The film’s centerpiece sequence, and arguably the apex of Stone’s career to date, sees Garrison getting the Deep Throat treatment from a mysterious ex-Black Ops official named “X,” with Donald Sutherland rasping life into page after page of exposition-heavy monologue, a relentless 20-minute tour de force. “X” leaves Garrison, and by extension the audience, slumped over, overwhelmed by the enormity of it all, but primed to carry the torch on his own obsessed terms, just as Stone climaxes the “X” sequence with LBJ signing the document that set into motion the Vietnam War that Stone famously endured as an Army grunt.

And it all ends at square one—with no convictions, no vindication, no assurance that any given bullet can’t do magic. Though its brute persuasion, JFK reveled in the darker impulses of the American psyche (i.e., tell me how to feel, so long as it’s angry), maybe the fullest manifestation of Richard Hofstadter’s The Paranoid Style in American Politics in action. But all it ultimately proves is that living history doesn’t have to be written by the victors. Merely the kooks who bellow with the most panache under the rockets’ red glare.

Image/Sound

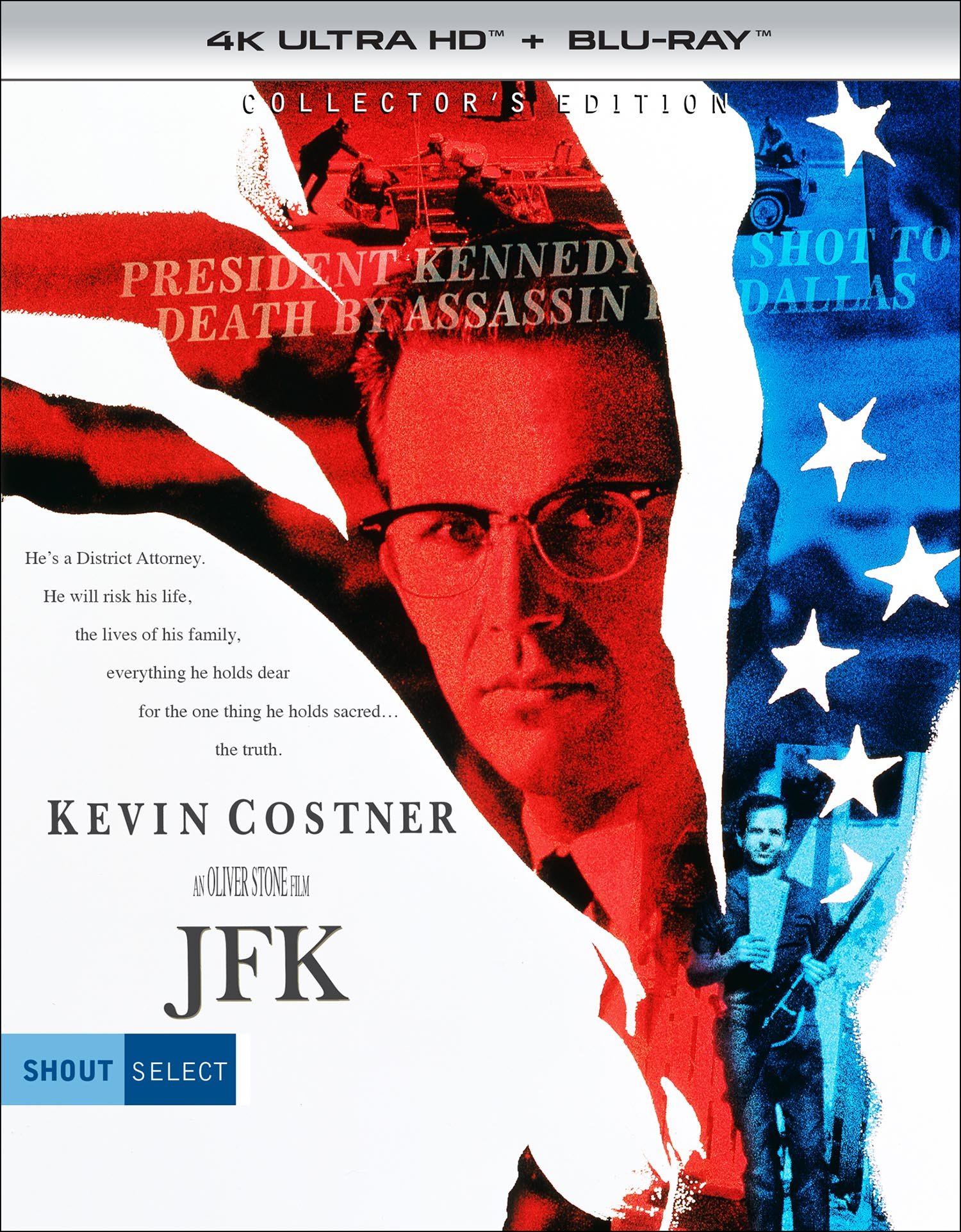

Oliver Stone’s preference for his “more cowbell” director’s cut has cut across every single home video format stretching all the way back to the VHS era. Derided for more than 20 years as inferior and meandering compared to the comparatively tight 189-minute version, the director’s cut only adds 17 minutes’ worth of content, none of it essential, most of it embarrassing (most notably the attempt to frame Jim Garrison in an airport-bathroom sting much like Larry Craig would experience four decades later). And throughout the film’s home video history, it’s the “more is more” cut that’s been given preferential treatment, with many disc-based releases not even including the theatrical option. So the good news, right off the bat, is that for the first time the original theatrical release version of JFK is available in HD physical media.

Unfortunately, even Shout! Factory’s attempts to craft a package that wrests a little bit of the narrative away from Stone and back onto the film itself couldn’t end the history of denigration for the better edit. Whereas the director’s cut is presented here in both 4K UHD and Blu-ray in a brand-new camera negative scan (the former in full Dolby Vision), the theatrical version is left unrestored, dumped onto a bonus Blu-ray disc. Comparing it against the full 4K upgrade isn’t quite as stark as the film itself—flipping back and forth from full-color anamorphic 35mm to monochrome Super 8 in an effort to trick viewers into thinking new footage is actually archival—which is a testament to the magnificence of cinematographer Robert Richardson’s Oscar-winning work on the film. But the difference is there. Colors on the 4K are vibrant and teeming, and the constant shifting of film stocks and processing is downright overwhelming.

In comparison, the Blu-ray of the theatrical cut, while clean and pressed, is akin to reading about the film instead of being immersed within it, given the image’s flatter color palette, and how its presented without the fizzy carbonation of palpable film grain. Happily, all versions boast DTS-HD master audio sound options, both surround as well as original stereo, all of which are intense and active. The bullet stinger that punctuates X’s monologue on LBJ signing the document that sealed America’s military escalation in Vietnam sounds like it travels straight through your heart, and the echoing reports of the drum corps rattling throughout John Williams’s restless score give Stone’s flights of fancy a remarkably sturdy foundation.

Extras

Attempts to make the director’s cut the “official” version of Stone’s epic weren’t the only indulgence that home video releases have been exacerbating over the decades. With each successive release of the film, the bonus features have increasingly moved into starring roles, to the point that JFK itself is being positioned as exactly what Stone suggested it was back in 1991: a warning shot, a mere prologue to a radical reimagining of what might’ve been had Kennedy not been struck by an assassin’s (oops, assassins’) bullets.

Some of the most recent home video iterations have come awfully close to using the film’s still potent reputation to smuggle all manner of “further reading” into the conversation. The luxe 50th anniversary edition made wish fulfillment and alternate histories its entire mission statement, going so far as to include the feature film PT 109 (starring Cliff Robertson as JFK in his soldiering years) alongside not one, not two, but three documentaries about JFK’s accomplishments in office. Shout! itself recently released a package of Stone’s recent JFK Revisited that many mistakenly thought also included the 1991 film.

In contrast, this box set comes on like a major corrective to that trend, to the point that it actually features far less bonus content than most of the other relatively recent editions. But the content it does include largely sticks to the appropriate lane: offering support and context around the story of the film, its making, and the immediate effects of its controversial release.

All three discs of the film are accompanied by the feature-length commentary by Stone, which has been in circulation since 2001, and is sort of akin to hearing him read aloud the annotations from his 600-page published screenplay. Rather than use the inclusion of the theatrical cut to give Stone, or anyone else, a chance to offer some fresh perspectives, Shout! merely cuts down the old track, despite it having clearly been recorded for the director’s cut.

The new content comes in the form of a half-dozen newly produced interview featurettes with various crew members, none of which broaches 10 minutes in length, most of which focus on the task of bringing Stone’s vision to life on the screen…except for Stone’s new clip, which finds him still frozen in conspiracy overdrive, albeit a tad calmer and more resigned than before. Aside from that, the set recycles an hours’ worth of deleted scenes, a featurette detailing developments in the investigation following the film’s release, and a short clip of L. Fletcher Prouty, the inspiration for X in the film, that somewhat proves how much easier it is to believe wild conspiracies when they’re delivered by Donald Sutherland’s graveled drone.

Overall

Even without A-listers Tommy Lee Jones, Joe Pesci, and Kevin Bacon playing shady gay conspirators, or a jive-talking John Candy crowing “You got the right ta-ta but the wrong ho-ho,” JFK still stands as possibly the purest camp artifact of American political cinema.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.