There’s a lot of promise in the idea of a musical starring Joaquin Phoenix and Lady Gaga playing the Joker and Harley Quinn, especially in the latter being portrayed as the ultimate unstable fangirl, and giving Arthur Fleck something to hope for as he goes on trial for the murders committed in Joker. Imagine what John Waters or Paul Thomas Anderson would do with that premise. Hell, we don’t even have to imagine an animated take, as Joker: Folie à Deux’s one true masterstroke of sinister, madcap joy is starting with a short recap of Arthur Fleck’s story created by The Triplets of Belleville director Sylvain Chomet.

When that short is over, though, we get the Todd Phillips version, which is largely anchored to stone-faced reality for 130-plus excruciatingly withholding minutes. In grappling with the implications of its story, Folie à Deux’s every attempt at showcasing cleverness, verve, or engagement is held underwater by staid direction, shoddy emotional plotting, a gleeful sense of cruelty, and a grave nihilism that makes Zack Snyder’s work seem like a season of Bluey.

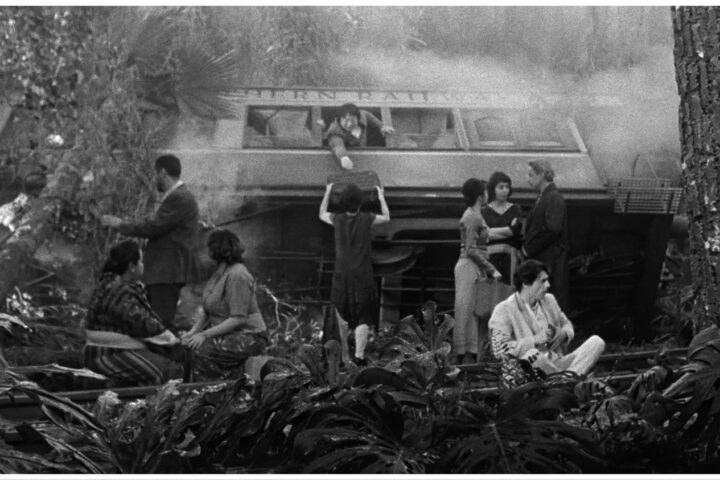

Phoenix’s Arthur, resigned to just floating numbly through his grim, ugly days at Arkham Prison, finds himself shocked back to life when he gets put into a music therapy class and meets Lee (Lady Gaga). Soon, the two are bonding over parental abuse, the horrifying crimes they’ve committed, and a deep desire for the rest of humanity to leave them both the hell alone. After their meeting, Arthur finds his daily routine intruded upon by musical performances in which he and his new crush duet across soundstages typical of old Hollywood.

Phoenix is no singer, but he’s such an intensely physical and emotional performer that he’s liable to convince you otherwise. For her part, Gaga brings power and subtlety to a role that otherwise reads as shallow, and she has plenty of chemistry with Phoenix. The two of them find simple, dancerly ways to express burgeoning, unspoken emotions through touch or movement or a look. Whatever strength lies in the film stems from their complete commitment.

But in the context of Folie à Deux, Lee is an emotional prop, something for Arthur to hyper-focus on while the world tries desperately to either condemn him or make excuses for his crimes. More than that, the musical numbers that clearly seek to invoke the Technicolor musicals of yore, and across which Arthur and Lee’s blossoming romance plays out, are flatly directed, denying the audience or Arthur any license to feel anything too deeply.

When the film is focused on Arthur’s day-to-day life as he goes back and forth from his prison cell to the courtroom, the unfocused editing between scenes makes it nigh impossible to tell where Arthur’s fantasy ends and reality begins, which may be the point given that Arthur’s self-delusion was a plot point of the first film. Joker wielded that idea sloppily and pointlessly, and that conceit adds next to nothing here in Folie à Deux aside from a confusion so pervasive that it makes it impossible to buy into, let alone grasp, what Arthur or Lee are even fighting for.

The real, deliberate answer may be “nothing.” In the end, Folie à Deux is a film caught between a rock and a hard place of its own creation. On the one hand, it’s obsessed with the non-controversy that making Arthur too relatable might create a real-life incel killer. On the other, it plays out as if making either Joker or Lee too funny, or their musical sequences too lavish, might make it too close to the comics and cartoons that Phillips has no real fealty toward.

Arthur falling back into old habits as his Joker persona should have felt powerfully dangerous, or dangerously powerful, as the film sets out to make us believe that society at large is on the brink of collapse because he’s just so damned popular. But this is cinematic centrism at its most cowardly and empty. When the climax of Folie à Deux finally manages to make a single intriguing statement about the platforming of amoral men, it’s far too little too late, and Phillips can’t even execute this without letting the film succumb to utter misery.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.