All credit to Mark Russell, the founding artistic director of the Under the Radar Festival. After the Public Theater, which has produced the international and experimental theater festival since 2006, dropped Under the Radar from its annual programming, Russell rapidly rebuilt. With no central home this season, the festival’s shows now crop up over a greater radius of the city, from smaller downtown venues like the Abrons Arts Center and Performance Space New York to major entities like BAM and Theater for a New Audience.

In its new iteration, Under the Radar, which runs through January 21, hasn’t missed a step. In fact, since so many disparate venues have programmed and produced shows this year, Under the Radar seems poised to introduce festival-wide fans to the curated tastes of theaters across New York, potentially growing year-round audiences too. There’s also the sense that the festival, partnering with producing theaters far more programmatically outré than the Public, now includes works that the Public might have blanched at supporting: Under the Radar’s offerings this year have a radical streak made possible by the storm the festival has somehow survived.

Voices Embraced

The festival’s tastiest morsel is Rose: You Are Who You Eat (La MaMa), a 90-minute memoir-ish musical from John Jarboe, an artist whose “gender is a little Sasha Velour meets Mighty Ducks.” Through this wistfully biting piece, Jarboe wrestles to unpack some family lore: While in the womb, Jarboe supposedly ate her twin sister, Rose. The uncovering of this pre-natal trauma prompts Jarboe to reevaluate an entire life’s gender journey through the lens of this unborn sister, a loss that’s both a running joke (there’s much cannibal humor here) and a shadowy presence genuinely mourned. “Sometimes I’m passing by a mirror and I wonder who ate who,” Jarboe sings in one of the show’s six stellar songs. Elevating the concept and ensuring it stays ripe for the duration, Jarboe surrounds herself with a mighty quartet of instrumentalists who also all sing backup (Daniel de Jesús, a cellist with a voice of gold, especially shimmers). The score, with lyrics by Jarboe and music credits shared among the band, is surprising and lovely, culminating in an audience call and response that could be heavy-handed but, under Jarboe’s artifice-free guidance, approaches near-transcendence.

Among a festival lineup tending toward the caustic, Jarboe’s warmth is a balm. There’s similar tenderness to Search Party (Lincoln Center), a not-quite-theater piece in which poet-playwright Inua Ellams solicits suggestions of words from the audience (think “grief,” “wonder,” “football,” “symphony”), before then searching on an iPad loaded up with his own poems, short stories, and essays. Every audience, of course, will hear him read different works aloud (an essay about Ellams’s early relationships with hip-hop and classical music was particularly stunning), but the real joy is that Ellams remains a poet between the poems: He’s a warm storyteller who introduces his work and then takes questions from the audience with an ever-gentle artistry.

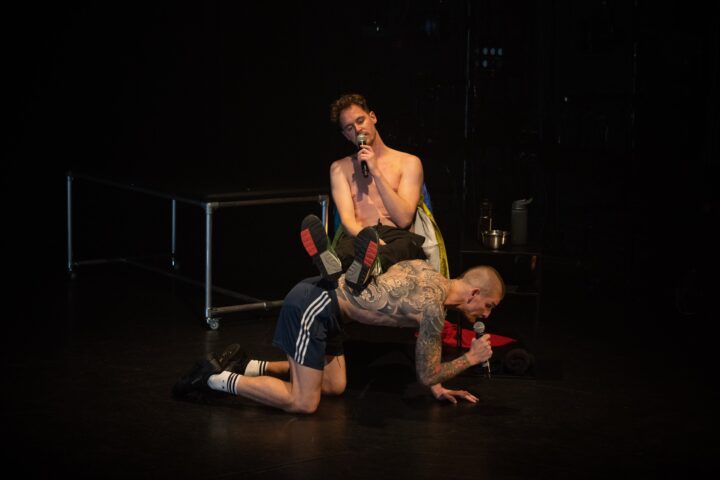

Peter Mills Weiss and Julia Mounsey’s Open Mic Night (Performance Space New York/Mabou Mines) plays fast and loose with the idea of being lovely to audiences. What begins as a self-parodic crowdwork—“Vipers or moles?” Weiss asks one audience member, trying to put us at ease as Mounsey critiques his tone—morphs into a sweetly sardonic elegy for the shuttered theater where the artists met. And in Queens of Sheba (Lincoln Center), a return engagement from last year’s festival, four Black British women celebrate their sisterhood through a rhythmically buoyant choreopoem of spoken word, song, and dance that feels tighter and more detailed than it did last year. “There is method to her melanin,” they repeat, an alliterative refrain of pride and support that stands in the face of the micro- and macroagressions in the workplace and dating arena described with humor and honesty throughout the piece.

Books Unlocked

Audience members pick a puppet of a child to accompany them before entering the theater for Krymov Lab NYC’s Pushkin “Eugene Onegin” in our own words (BRIC). This is, after all, the four Russian theatermakers insist as they storm the stage with bags of props and costumes in tow, a children’s show. Their mission is to ensure that Alexander Pushkin’s novel Eugene Onegin isn’t forgotten beyond Russia by the next generation—and with the-show-must-go-on zeal, the quartet overcome the interpersonal rifts that keep bubbling up between them, to bring the novel to life. Director Dmitry Krymov’s metatheatrical jokes are whip-smart and the cast unfurls them with delight. The show, which undergoes a bit of a tonal shift in its final quarter, doesn’t quite stick the landing nor fully integrate a message about the war with Ukraine, but the fizzy humor and jocular embrace of the stage’s imaginative possibilities prevail.

For Dublin-based company Pan Pan’s The First Bad Man (Lincoln Center), audience members are encouraged to do their reading first. The play depicts a book club analysis of Miranda July’s gracefully disturbing 2015 novel of the same name about a woman whose strange fantasies spill over into bizarre relationships. If you haven’t read The First Bad Man, you’ll be at something of a disadvantage, because even if you can keep up with the plot as the cast enacts a rapid-fire impromptu performance of the book in order to “exorcise” the haunting protagonist, you’ll miss out on the memorable narratorial voice that makes July’s novel worth reading in the first place. Pan Pan, despite some amusing non sequiturs and appealing quirky performances as four readers try to make sense of the book, never makes a clear case for why this book or why this group of faintly drawn characters exploring it.

Audiences Ambushed

“Any Lenape here?” Cliff Cardinal asks, stepping in front of a curtain to give a land acknowledgment (“I fucking hate land acknowledgments”) at the start of William Shakespeare’s As You Like It: A Radical Retelling of Cliff Cardinal (NYU Skirball). There’s no response. “Violence displacement going well,” he concludes. Suffice it to say that Cardinal, who’s Cree and Lakota, has no intention of delivering As You Like It as Shakespeare intended. Instead, he takes us on a ride with one gloriously sly speed bump of a twist that gets at the heart of what it means to be a theatergoer and maybe also what it means to be fully free in America. Cardinal’s not the gentlest presence; if he comes across as bitter or unlikeable, that’s kind of the point, as he unapologetically admits deep into the show. At the same time, Cardinal’s story- and truth-telling around experiences of indigeneity are defiantly earnest. Once you accept the show’s central surprise act of mischief-making, it’s hard not to take note.

Toward the beginning of As You Like It, Cardinal seemingly calls out the festival itself (“They gave us the building and walked away”), but there’s a far more cutting critique of the institutions producing theater in this house is not a home (Abrons Arts Center), a co-commission of the Abrons Arts Center and Ping Chong and Company. In the funniest, most direct portion of a piece that’s otherwise more memorable for its disarming visuals (a gingerbread man carrying a transistor radio in front of a portrait of George Floyd, a bouncy castle deflating as two lazy Gen-Z white women hop around inside), the show’s creator, Nile Harris, mercilessly mocks the grant process that funded the piece and critiques Abrons Arts Center’s artist compensation model. “You can’t make anything radical within a nonprofit theatrical model,” he asserts.

Then, though, Harris unleashes Crackhead Barney on the audience. She’s a no-holds-barred ambush interviewer (who’s infamously crashed Trump rallies, including a confrontation with the “QAnon Shaman” on January 6). As Barney, in gray full body paint, clambers through the audience with a microphone while pepper-spraying increasingly off-putting questions (“Are you anti-Semitic? I am!”) for minutes at a time, the wider piece, including Harris’s physically and emotionally rigorous performance, recedes into the background. Although there are flashes of unsettling and piercing clarity, especially in Harris’s section of the show, this house is not a home tilts too dramatically toward its most uninhibited performer.

Albert Ibokwe Khoza’s The Black Circus of the Republic of Bantu (New York Live Arts) is a lot more specific about what the audience is there to confront—the legacy of Africans forcibly displayed as “freak show” attractions for Western audiences deep into of the 20th century—but offers uncomfortable distractions that undermine the show’s pointed storytelling and Khoza’s stirring presence and movement. Tying audiences’ hands together as they enter is harmless, even if ineffective at communicating the horrors of these disturbing expositions. But when Khoza gets completely naked and embraces every audience member with no consent or warning, the performance loses its moral gravity. By delivering a performance that is itself violatory, Khoza pushes the historical violations farther away, not closer.

Volcanoes Erupted

What does it mean to be human? Inside a glass prism that takes up the entire stage, two men (Luke Murphy and Will Thompson) seemingly try to answer that question, acting out iconic moments from film and TV history and dancing with abandon to wide-ranging radio hits. They’ve been seemingly tasked with absorbing an “almanac” of quintessential cultural references that make us who we are. The threads of why exactly they’re in this box and who’s put together this playlist will unspool throughout the four-hour-plus runtime of Volcano (St. Ann’s Warehouse), conceived, directed, and choreographed by Murphy to have the pacing of a miniseries (the show’s delivered in four equal-sized chunks that end on cliffhangers).

And while the sci-fi plot revelations (shades of Olivia Wilde’s Don’t Worry Darling) remain fairly fuzzy, Murphy’s staging is spectacular and never less than engrossing. Each episode contains an extended pas de deux or solo dance segment, and Murphy and Thompson excel at imbuing their bodies with the story’s emotional intensity, even if the connection between dance and dialogue is sometimes more impressionistic than literal. More so than anything else in the festival, Volcano feels startlingly sui generis. With its own theatrical genre, filtered through the physicality of dance and the structure of television, it’s calling out for a second season.

Nearly as wild—but about 20 times goofier—is Hamlet | Toilet (Japan Society), Yu Murai and Kaimaku Pennant Race’s Japanese-language tribute to literature’s crown prince of indecision, a state here represented by constipated bowels. Until Hamlet revenges himself on Claudius, according to his father’s ghost, which is now nested snugly in Hamlet’s intestines, the prince will not be able to complete his lavatorial mission, so to speak. Disgusting? Sure. But, clad in white latex body suits, the three performers gamely embrace a script that’s one-third Hamlet, two-thirds toilet. Some of the more opaque gestures—like staging Claudius’s confession beneath a gravel pipe that rains rocks on his head and the repetition of some scenes five or six times in a row—drift Hamlet | Toilet away from amusement toward annoyance. But when the fart-filled script most vigorously engages with the silly task of injecting fecal matter into the world of Shakespeare, the results can be gleefully and winningly absurd.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.