Made in the midst of his run of feverish, postmodern genre films at Nikkatsu, Suzuki Seijun’s Tattooed Life is something of a snapshot of the more patient, probing works that the filmmaker made in the 1980s and beyond. It starts, though, at a frenzy, with yakuza hood Tetsu (Takahashi Hideki) set up from the jump by his bosses to carry out a hit on a rival that’s also meant to sacrifice him as a patsy. His brother, the sensitive and soft-spoken artist Kenji (Hananomoto Kotobuki), ends up killing the other yakuza to save Tetsu, forcing both to flee from both rival gangs and their own superiors, who are seeking to tie up loose ends. Further double-crosses follow as the brothers are conned by gangsters and everyday charlatans making false promises of safe passage to Japan’s Manchuria colony.

The brothers do eventually make it to Manchuria, where they hide out in a rural mining village upon ingratiating themselves with the de facto leaders of the community: the Kinoshita family. The Kinoshitas are a legitimate entity, forcing Tetsu and Kenji to conceal their true identities and Tetsu specifically to keep his elaborate yakuza tattoos under wraps, so that they can at least pass as run-of-the-mill drifters. But Suzuki never lets the audience forget that the clan exists on the edge of Japan’s colonial frontier at the outset of its brutal campaign in China in the 1930s, and the friendly relations that family head Yuzo (Yamanouchi Akira) has with local authorities offer a constant reminder of the symbiotic relationship between military might and private commerce that subjugate others for the sake of territorial expansion.

That subtext, though, simply looms in the background, and it all but disappears from view after the narrative pivots to focus on Tetsu and Kenji’s respective romances with Yuzo’s sister-in-law, Midori (Izumi Masako), and his wife, Masayo (Itō Hiroko). The former relationship operates as a more conventional romance, with Midori gravitating toward the taciturn, protective Tetsu as an escape from the kind of loveless marriage that Masayo endures. All the while, Tetsu tries as hard as he can to keep her from finding out his status as a gangster.

By contrast, the bond that forms between Kenji and Masayo is more abstract and psychologically fraught. The young artist sees Masayo as the image of his mother, who died before he got to knew her, and his neurotic attraction to Yuzo’s wife arises from a kind of vestigial Oedipal desire, as evinced by him wanting to sketch the woman nude. Masayo, for her part, is so drawn to being needed by a man that she reciprocates this fixation with equal verve.

Tattooed Life’s turn toward the psychosexual places it firmly within the outré limits of the Japanese New Wave alongside the work of mavericks like Oshima Nagisa and Imamura Shohei. It certainly reveals a side to Suzuki that wouldn’t fully manifest until nearly two decades later, when he returned from a long career exile with his Taisho trilogy. Like those films, Tattooed Life adopts a sedate visual grammar that distinguishes it from his contemporary gangster parodies for the way they really sit with the characters’ complexities and contradictions.

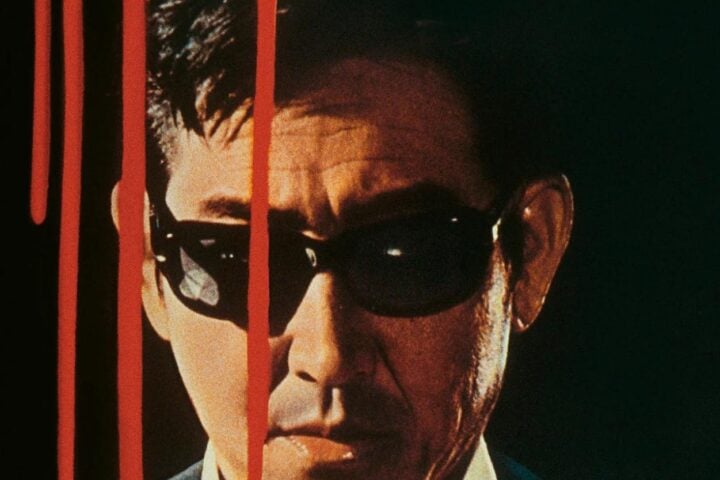

Nonetheless, the film does contain a number of trademark instances of Suzuki’s capacity for surreal phantasmagoria. The opening assassination is a frenetic duel between henchmen disguised as rickshaw drivers that’s half-fight, half-race, and the use of bold color throughout places the film comfortably within Suzuki’s other splashy chromatic features of the era.

Nothing, though, compares to the climax, in which the protagonists’ identities are finally exposed by their old compatriots, leading to a showdown between Tetsu and his old clan in which the hero moves through various rooms in a compound that are each explosively bathed in a different color. As Tetsu goes from room to room via sliding shoji screens, the sequence begins to look like a series of Piet Mondrian paintings, with the camera taking on a litany of wild positions, eventually ending up below the combatants as they shoot up through a see-through floor. It’s one of Suzuki’s wildest set pieces, upending the uneasy placidity of the first hour in a way that conveys all of Tetsu’s horror and rage at having his second chance at life obliterated.

Image/Sound

The transfer by the fine folks at Radiance Films balances the film’s moments of naturalistic exterior tones of greens and browns with the jolts of vibrant reds, blues, and yellows of everything from costumes to the filtered lighting of the ending sequence. Detail is clear and film-like throughout, with consistent grain distribution and stable black levels. The mono soundtrack foregrounds dialogue amid the occasional burst of action sound effects and music while leaving ample negative space to emphasize the tranquility of the rural setting.

Extras

The disc comes with an audio commentary by Suzuki Seijun scholar William Carroll that’s rich in details related to the filmmaker’s career and aesthetic, as well as Nikkatsu’s output at the time of Tattooed Life’s release. An excerpt of a 2006 interview with Suzuki discusses his approach to filmmaking during the mid-1960s and how he attempted to convey the tumult of the era in his style, humorously adding that he was never good at conveying realism. In another interview from the same year, art director Kimura Takeo delves into his background in theater and how his collaborations with Suzuki pushed his craftsmanship in a more surreal direction.

The accompanying booklet comes with an essay by critic Tom Vick, who contextualizes Tattooed Life as the fulcrum separating Suzuki’s daring yet relatively straightforward genre films and the fully abstracted work of his final stretch of films with Nikkatsu. Also included is an archival contemporary review by Japanese critic Fukusawa Tetsuya, who scrutinizes the bafflement with which the domestic critical establishment received the filmmaker’s work at the time.

Overall

An overlooked curio from Suzuki Seijun’s mid-’60s run of films receives an excellent transfer.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.