Midway through Bob Clark’s Deathdream (originally titled Dead of Night), Andy Brooks (Richard Backus) dons a pair of black leather gloves and sunglasses for an upcoming date. Andy displays a suave and calm demeanor that should be familiar to fans of Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1967 film Le Samouraï, which features Alain Delon as the ne plus ultra of psychotic cool; his haircut even recalls that of Steve McQueen in 1968’s Bullitt. However, Andy’s garb has a tactile purpose, concealing as it does his deteriorating skin, which will turn to dust without a replenishing supply of blood. Because of this, Clark’s genre film goes in the opposite direction of peddling cool, as Deathdream shows how a pair of designer shades can only momentarily shield the irreparable physical and psychological scars of war.

That Deathdream is a vehement anti-war statement can only be ascertained gradually, as Andy’s parents, Charles (John Marley) and Christine (Lynn Carlin), fall to pieces realizing that their son, who’s just returned from Vietnam, is somehow not the same man who left years ago. Clark and screenwriter Alan Ormsby create scenes that complicate a concrete sense of time and place, from the elliptical opening credits sequence depicting Andy’s death, to the logistics of his seemingly miraculous resurrection and arrival at the Brooks household. When Andy suddenly appears during the middle of the night, Charles has a pistol in tow, ready to shoot an intruder on sight. That Andy also died from a gunshot wound factors into the filmmakers’ darkly ironic sense of humor: Had Charles recognized immediately that this figure wasn’t actually his son, the law would paradoxically exonerate him for pulling the trigger.

In the film, violence thoroughly intertwines with American identity. When the neighborhood postman (Arthur Anderson) realizes that Andy has returned, he flops down in a lawn chair and begins waxing poetic about his days during World War II. Talk of war and sharing battle scars, especially as a source of pride, prevents anyone from immediately realizing Andy’s transformation into a non-human entity—one who’s more vampire than zombie. The distinction crucially enunciates Andy’s attempt to withhold his condition; he’s like Dracula, descending upon Carfax Abbey and its surrounding territories to bleed the innocent dry. Deathdream must be understood as a film likening the warmongering mindset of American life to pestilence, one that returns in cycles to decimate each new generation of idealistic young men.

Andy’s arrival particularly affects his mother, whose initially inexpressible joy at seeing her son in one piece subsequently morphs into a willingness to lie about her son’s condition and enable his murderous behavior. Clark shoots Christine as a particularly fragile woman, leaning on close-ups of her withered visage so as to home in on her desperate hope that her homestead might become normal once again. The family’s attempts at normalcy include a botched surprise by Andy’s sister, Cathy (Anya Ormsby), to reunite him with Joanne (Jane Daly), the girlfriend he left behind. It’s as if the Brooks family and their entire small town’s inability to conceive of a life beyond the past conjures this new Andy as a punisher of the repressed.

Deathdream is one of few American films that provides no outlet for its characters’ grief; the Brooks family seem like helpless rats trapped in a maze without an exit point. That sense of their helplessness may can be attributed, in part, to the fact that the filmmakers never chalk up Andy’s death, and his family’s suffering, to any greater purpose or code of valiancy. On the contrary, Andy’s return as a vampiric clone of himself lays bare a militaristic mindset as one defined by violence toward the helpless (Andy murders the family dog in front of a group of neighborhood kids). Yet, Andy, writhing in a grave and wasting away during the film’s closing minutes, can only be deemed a villain in the most literal sense, because the dream master—whatever entity pulling the strings, whether spiritual or secular—never steps forward.

Image/Sound

If the new 4K scan that Blue Underground has bestowed upon Deathdream isn’t a substantial upgrade over the studio’s prior 2K presentation, it’s because that one looked pretty damn good. Especially in native 4K, the clarity and depth of the image is superlative. While there were a few scratches and blemishes on the image of the 2017 release, they have been mostly eliminated here. Grain is lovely and healthy, giving the film an almost docu-realistic quality. The DTS-HD monaural soundtrack, ported over from the 2K restoration, won’t shake your speakers, but it successfully balances dialogue and score without any audible defects or drops in volume.

Extras

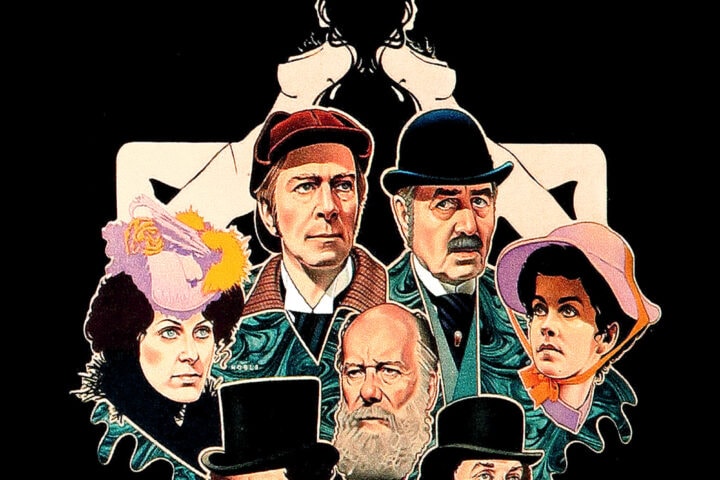

All the extras from Blue Underground’s excellent 2017 Blu-ray have been ported over to this release, along with a new commentary and a new interview with actor Gary Swanson. The first commentary features Blue Underground co-founder David Gregory and director Bob Clark, recorded for the studio’s 2004 DVD release. The pair marches through the film’s production and other various bits of trivia. Most of it, including the fact that a different actor plays Andy during the dark and murky opening sequence than in the rest of the film, proves rewarding and will deepen anyone’s understanding of Deathdream’s contribution to 1970s American horror.

The second commentary also features Gregory, this time speaking with screenwriter Alan Ormsby about some differences between his original script and the final film. The new commentary allows film historians Troy Howarth and Nathaniel Thompson the chance to simultaneously reflect on their individual experiences with and opinions of Clark’s films, while also conveying the various creative efforts that went into making Deathdream.

A whopping eight featurettes run the gamut of the film’s production and legacy. Some of the information contained within them overlaps with the thoughts and insights revealed in the commentaries. Others, such as those featuring interviews with composer Carl Zittrer and star Richard Backus, focus on various aspects of the production from other helpful vantage points. There’s also a brief interview with makeup titan Tom Savini, who explains his influences and the origins of his obsession with perfecting the art of on-screen bloodletting. The remaining extras are mostly minor: alternate opening credits, a theatrical trailer, still galleries, a screen test with Swanson (the actor originally cast as Andy), and an untitled student film by Ormsby.

Overall

Blue Underground gives Deathdream an impressive 4K upgrade, along with an array of extras that cover every possible angle of Bob Clark’s cult classic.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.