Ethan Hawke’s Wildcat won’t tell you much about what Flannery O’Connor accomplished. The audience won’t learn about O’Connor’s place in the literary world, the larger culture, or alongside other consciously Catholic fiction writers like Graham Greene. There’s a worthy determination to the way that Wildcat sees O’Connor’s world almost entirely from her mystical, pain-rattled perspective. But by limiting the film’s viewpoint so strictly, Hawke and co-screenwriter Shelby Gaines miss an opportunity to introduce O’Connor to a wider audience.

Hawke’s gnomic biopic opens with a 24-year-old O’Connor (Maya Hawke) trying to make it in New York, circa 1950. Having won a literary prize while attending the prestigious Iowa Writers Workshop, she’s trying to get her first novel, Wise Blood, published. But O’Connor, incapable of small talk or artistic compromise, isn’t a striving literary ingenue working the angles and currying favor. When she rejects the changes that John Selby (Alessandro Nivola), editor-in-chief of Rinehart Company, thinks will make her work more commercial, he declares that she’s “trying to stick pins in your readers, trying to pick a fight.” He’s condescending but not wrong.

The O’Connor of Wildcat is a contentious outsider who seems ill at ease in her own skin. Too country Southern and gawky for New York, and too Catholic and idiosyncratic for the hidebound, keeping-up-appearances Protestantism of her native Georgia, she seems only somewhat at peace when putting stories on the page. As played by Maya Hawke, O’Connor is perpetually agitated, her thousand-yard stare reflecting the fervid visions and theological wranglings that bang around in her mind, suggesting more a rebellious mystic than an artist.

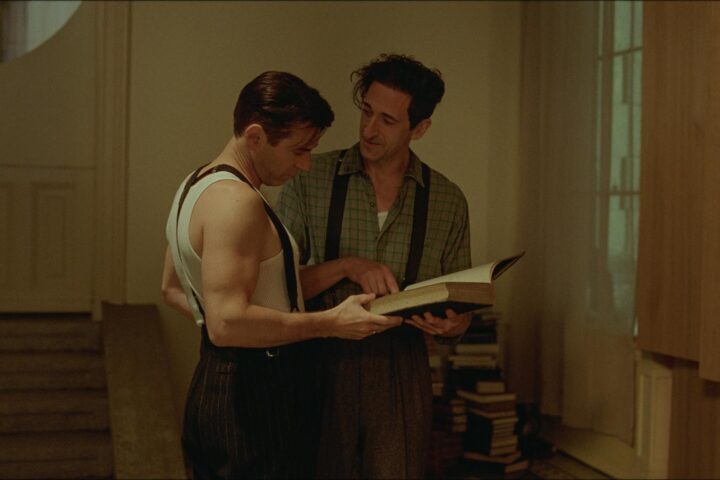

The rough outlines of O’Connor’s biography are visible in spots, with a few scenes detailing her friendship and unrequited romance with her teacher and advocate, the poet Robert Lowell (Philip Ettinger). But the film’s plot is relatively limited in scope, with Ethan Hawke and Gaines (who also co-composed the music) basing the screenplay largely on O’Connor’s stories. Not long after the opening New York sequence, an increasingly sickly O’Connor leaves for her childhood home. There, she scraps with her mother, Regina (Laura Linney), and wrestles with her writing while dealing with the lupus that kept her largely confined to the house for the rest of her life.

That semi-imprisonment happens relatively early. From that point on, Wildcat is largely made up of the fictions which play out in O’Connor’s mind like short plays produced by a small theater company. Reflecting the narrow circumstances of O’Connor’s life, Linney and Maya Hawke play different characters in each. A rotating cast of actors, among them Steve Zahn, Rafael Casal, and Cooper Hoffman, play the slightly addled and charismatic yet predatory men who populated O’Connor’s fiction, haunting and hunting its female characters.

These symbolic melodramas depict tight-knit, contentious families and couples whose lives are wracked by visions, trickery, violence, hate, and suspicion. By shooting the fiction sequences with the same dreamy fish-eye unreality as the scenes showing O’Connor’s real life—automobiles and telephones are the only nods to the 20th century, otherwise we might as well be in antebellum times—the film blurs the line between the two until it’s almost nonexistent.

This is an effective trick for sticking us in O’Connor’s head, generating an experience that’s claustrophobic, difficult to map, and thick with religious angst. “What people don’t understand is how much religion costs,” she says at one point. “They see it as a big electric blanket when in fact it’s the cross.” Wildcat effectively shows how for O’Connor the mystery, pain, and loneliness generated by her writing pursuits are twined so closely with her agonized faith.

In one poignant scene, O’Connor is visited in her sickbed by an Irish priest (Liam Neeson). The two talk of seeking God and the merits of James Joyce, topics that, like much of Wildcat, are complex, inscrutable, and can lead to tail-chasing but occasionally provide moments of grace.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.